A "liberal America"? That's what John Judis is calling our country now, and he's got a point--several of them, in fact. Many of them, perhaps the majority of them, I'm happy to agree with...but some I'm most certainly not.

I agree that there are good historical reasons for seeing the election of Barack Obama as the distillation of a potentially strong and long-lasting realignment in American politics, perhaps as strong as the one which gave the Democrats dominance over the federal government for decades following FDR's election in 1932, mostly having to do the cyclical nature of such periodic alignments. But is there real data to support Judis's historical analogies? Well, there is some. Judis--along with his occasional partner, Ruy Teixeira--has been arguing for years that demographic trends in America are placing the shape and destiny of our national politics primarily into the hands of highly educated professionals (the great majority of whom work in knowledge or arts-based service industries), working and/or single women (most of whom are also college educated), and minority ethnic groups. Moreover, all of these demographic slices of the electorate are predominantly relocating to "ideopolis" urban areas--high-tech metropolitan cities surrounded by extensive exurbs, like Denver-Boulder, Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill, and so forth. And all of these trends seemed present and very much accounted for on Obama's election night. If you rank all the states on the basis of their percentage of people with advanced degrees, Obama won all of the top twenty (for 232 electoral votes alone). Nationwide, he won the votes of all women 56% to 42%, and of working women by 61% to 38% (a close to two-thirds majority). In regards to ethnic minorities, he predictably won a huge majority of the African-American vote, but he also won Hispanics and Asians by a spread of nearly or more than 30 percentage points in each case. In fact, some of the data seems to suggest that it was Obama's success with these groups alone, without any significant change in the non-Hispanic white and/or "working class" vote, that brought him the votes to win states which Kerry lost to Bush in 2004. Thus, it all seems to point in the direction of Judis-Teixeira's conclusion: the balance of electoral power is moving away from those traditional constituencies which built the primary elements of both the New Deal coalition and its predecessors, as well as the "Reagan Democrat" backlash (white, and/or European ethnic, traditional Christian, Southern and Midwestern, blue-collar and/or rural workers), and into the hands of those whose worldview, vocations, educations, and lifestyle choices are thoroughly aligned with a globalized world. In short, "the heart of the new majority is no longer blue-collar workers, but the professionals, minorities, and women who live and work within post-industrial metropolitan areas [italics added]....[Their beliefs] are socially liberal on civil rights and women's rights; committed to science and to the separation of church and state; internationalist on trade and immigration; skeptical, but not necessarily opposed to, large government spending programs, particularly on health care; and gung-ho about government regulation of business, including K Street lobbyists." This is a progressive majority that, as Ezra Klein writes, "look[s] like the America we expected to see tomorrow, not the America we remembered from yesterday."

I suppose I could be happy with this diverse and new majority; after all, it won Obama the election, and, as Matt Yglesias suggests, it may promise to win him and candidates reflective of a similar multi-racial coalition more of the same in the future. And to be sure, I'm not necessarily unhappy with all that; I particularly like--but of course, I would--Judis's acknowledgment that there is a "Naderite" streak in this new electoral grouping, in that it appears strongly committed to advocacy and participation and a distrust of those corporations and social structures which get in the way of the voices of consumers and voters being heard. But taken as a whole, I must admit I'm also a little suspicious of it, and little depressed about it. I've expressed my (perhaps desperately willed) disbelief in, and my opposition to, the Judis-Teixeira thesis several times before; I find it a condescending and misguided appreciation of what both community respect and social justice require, dealing as it does with the assumption that progressives can either count on the American working class absorbing the professional, centrist liberalism of their better-off cultural superiors, or else that they should simply plan on avoiding anything that smacks of reaching out to the (usually still church-going) working poor and lower-middle-class, both black and white (and that means unionization, anti-free trade policies, vouchers, faith-based initiatives, etc.), because doing so could turn off their new upscale electoral base.

But perhaps all this is inevitable. After years of continued globalization, years of collapse in rural populations, years of immigration, and, perhaps especially, eight years of the Bush administration--an administration that in so many ways (some intentional, some not) helped to work up the red-state/blue-state divide along class and cultural and religious lines, with the result that plenty of perfectly ordinary white middle-class exurban professionals recognized themselves in those accusatory labels: upscale, egghead, liberal elite--well, who would be surprised that the predictions of Judis and Teixeira appear to be bearing fruit, with these voters accelerating their movement towards mainstream liberal candidates? The "conservative" elements of their professional, exurban, bourgeois lives were being ignored or read out of the conservative cocoon which grew up around and through Bush's years in office. (I'm reminded of the frustrated realization felt by conservatives like John Schwenkler, Rod Dreher, or Ross Douthat when it became apparent that elements of the conservative machine had a problem with them them just for, say, assuming that everyone ought to like good healthy food, or that everyone ought to want to be exposed to different cultures, or for making the obvious point that populist politics ought to be balanced with "elite" book smarts.) Sounds like a recipe for a new majority to me, as much as I may be frustrated by parts of it. And as for the folks I tend most to trust and like, the old school, rural or ethnic populists, progressives, and New Dealers, the deep (often conflicted but always present) Laschian backbone of the 1932 (and, in an inverse way, the 1980) realignments? Well, perhaps they can be just forgotten. Why not? Doesn't this election conclusively prove that Democrats can win without the non-Hispanic white and/or working-class South, and all its white "homelander" traditionalists/populists? Perhaps it does.

But then again, maybe I shouldn't say that the liberalism of Judis and Teixeira has triumphed quite yet; maybe all that triumphed was Obama over Bush. Leaving aside the frame provided by Judis's analogies, it's clear that his victory wasn't that large of a sweep: a difference of about 7.5 million votes separated them, or about 6% of all votes cast. Besides the impressive (for Obama, anyway) developments amongst non-white voters, little fundamentally changed: the rich and the South still voted primarily for McCain, young people still didn't turn out in large numbers, and the basic red-blue geographic distribution of votes didn't change much--enough to flip a few close swing states, obviously, but not much more than that. Obama's victory did not translate into big wins in Congress. Perhaps most revealingly, on several key culture and social referendums across the country, you had a majority voters (including a fair number of white voters, of course, but in particular large majorities of religiously inclined black voters as well) supporting Barack Obama while at the same time endorsing positions that on first glance don't fit together under the umbrella of the kind of urbanized, secularized, professionalized egalitarian liberalism Judis takes his win to represent: voting against gay marriage (in California, and elsewhere) on the one hand, and for better public transportation and laws regarding the prevention of cruelty to farm animals on the other. Of course, there is one label under which I, at least, could argue that high-speed rail and traditional marriage and humane food production all fall...and that's Rod Dreher's crunchy conservatism, of which I'm a fan. But it's hardly likely that a movement as focused on things traditional and local as Rod's could really do something, ideologically or electorally speaking, with a pattern of votes like this. More likely, a different frame is going to be needed: a different way of expressing and packaging those voters which Obama picked up and which whom he shares so much ideological and demographic territory, but which also seems to reflect priorities that don't quite carry all the way through with the liberalism which Judis predicts (and has long been waiting for). It would have to draw upon the existing tendencies towards "crunchiness" out there, but which also--I hope at least--makes space for the sort of populism that Obama's liberal America, in reference to all of the above, might well touch upon, but which as yet may not be coherent enough to drawn out of him the way I'd like to think it could be.

When I first picked up the phrase "left conservatism" I was mostly just making a theoretical argument, one with only incidental relevance for actual politics; it was a frame to lump together a huge range of superficially dissimilar, but I would argue deeply connected, "socially traditionalist" and "traditionally socialist" political motivations, to use a couple of overly general labels for it. Christian social democrats, Red Tories, egalitarian populists, various "Third Way" and communitarian types--really, just about anyone who, whether they articulate it this way or not, rejects some of the more individualistic and/or secular presumptions behind many modern liberal arguments, and thus are interested community empowerment, unionization, participatory democracy, parental involvement in education, civil service, anti-consumerism, progressive taxation, media responsibility, fair trade, civic religion and respect, localized and decentralized bureaucracies, limitations on corporate power, and so forth...all could be captured by this umbrella. Obviously, it describes a very different (ideologically, at least; perhaps less so demographically) umbrella coalition of progressive voters than does Judis and Teixeira's, and--given America's political culture--a far less likely one as well. Obama, in so far as anyone can reasonably guess, wouldn't place himself under this coalition. So it's probably not going to be of any use in analyzing what happened this week and where American politics is apparently heading from this week forward; certainly it's not likely to help organize efforts to capture, respond to, or even direct the movement (however large or small) which Obama's win may (hopefully!) have begun. (Which is too bad; if that were the case, I could probably snap up a book contract real quick.)

So why bring it up? Because the crunchy cons and reactionary radicals and dissident leftists and conservative Democrats out there have a few of choices before them. They can push for legislation and initiatives and habits of behavior which may work against the demographic and socio-economic trends that Judis's analysis depends upon, so as to make that kind of liberalism less dominant in our political life and less controlling of Obama's agenda and those of his successors: stricter immigration policies, more support for rural life and blue-collar industries, a more pro-natalist tax code, etc. Let's call that Douthat's and Reihan Salam's "Reform Conservatism" option. But maybe the compromises with modernity therein are too much--and strategies involved too beholden to a party and a political language which Bush has thoroughly discredited--to really engage the scattered progressives that Judis, et al, are more than happy to lump together which what they see the new, inevitable, perhaps already-arrived America. So, instead, they can look to investing in their own local or familial retreats from the changing culture, happy to make use of the best, most progressive (in some ways) parts of it, but otherwise just hoping to tend to their own gardens. This, of course, is Dreher's "Benedict" option. It's an appealing one...but, for me at least, I think our obligation as moderns--and as Christians--to attend to and make something more justice and more beautiful and more equal out of the interconnectedness we have inherited requires more than small-scale solutions, however radical they may be and however worthy and important in their particular ways.

So that leaves me thinking that, if we who care about conserving communities and raising our children right, but who also care about the best elements of the liberal possibilities we have before us, who voted--sometimes in the midst of religious or personal or moral conflict and doubt--for Obama, who supported for both Proposition 8 and Proposition 2 in California, who wanted to be part of a change in our politics and policies in the direction of something more respectful and responsible, more deliberative and civic-minded, and most of all more humane and communal...well, our only option is to try to rethink and repackage populism for a world where so much of what made the old egalitarian conceptions politically viable is going or gone. Rod, for one, expresses respectful doubts; he just doesn't see any kind of thoroughgoing populist rethinking as plausible in an America as diverse as ours is today. He may be right. Maybe there can be no populism--not a "true and defensible populism" anyway--in a political world where rural and working-class voters (white or black or otherwise, Christian or otherwise) are all caught up into--and are embracing!--a social environment that, for all its current problems (and they are many), is still far more liberated, far wealthier, far more mobile, far more individualistic, far more aspirational, and far less disciplined, than that which existed thirty years ago, much less seventy, much less a hundred. And no, I don't hope for a war or a peak oil apocalypse to force us back to those conditions (though the latter may be unavoidable at this point); John Holbo nailed the perverse complications of a conservatism that secretly longs for those kind of crises long ago, and I don't want to even gesture in the direction of such. No, we're moderns (we're blogging, after all, aren't we?), and that means we are, in a small but essential way, already liberal, already attuned to individual liberty and the diversity and prosperity and technology which both supports and follows such. So no, I'm not going to try to delude myself into believe that there's wholly original kind of liberal communitarian politics available for Americans today on a broad basis, one which is just hidden within all this voting data (or within myself, for that matter), just waiting to be articulated. But neither am I going to throw in the towel of rethinking. I'm a theorist, after all; it's what I do.

Obama's progressive and mainstream liberal Democratic politics are going to be good for this country, in many ways, and that means good for many of its citizens, wherever they place themselves in the midst of all this political reflection (assuming they even both to do so, which probably would be a waste of time for most). And as he attempts to implement them, I trust he won't forget the what Bill Clinton knew--that however cosmopolitan American may be becoming, culturally populist and localist religious believers can be a part of a progressive coalition too. Obama just about made up all the ground which Al Gore and John Kerry lost amongst evangelicals, particularly amongst the more communitarian and engaged believers in the Midwest and the West as opposed to the South. And then of course there is Obama's improved performance amongst Catholic voters. Certainly, all these progressive and liberal and believing Christians aren't going to let him forget! So perhaps these believers, black and white and otherwise, many who are foot soldiers in an emerging demographic change in American Christianity, can also--at least a few of them, at least some of the time--contribute to making sure the new liberal America, whether it's already here or merely on its way, doesn't completely lose the popular and cultural aspect as it moves (again, hopefully!) into a more sensible, more egalitarian, more progressive response to our complicated world. A hard thing to work toward, but not an intellectually or politically impossible thing. Yes we can.

Alexander

Alexander  Listeners of radio’s Columbia Broadcasting System who tuned in to hear a Christmas Eve rendition of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol were shocked when they heard what appeared to be a newscast from the north pole, reporting that Santa’s Workshop had been overrun in a blitzkrieg by Finnish proxies of the Nazi German government. The newscast, a hoax created by 20-something wunderkind Orson Wells as a seasonal allegory about the spread of Fascism in Europe, was so successful that few listeners stayed to listen until the end, when St. Nick emerged from the smoking ruins of his workshop to deliver a rousing call to action against the authoritarian tide and to urge peace on Earth, good will toward men and expound on the joys of a hot cup of Mercury Theater of Air’s sponsor Campbell’s soup. Instead, tens of thousands of New York City children mobbed the Macy’s Department Store on 34

Listeners of radio’s Columbia Broadcasting System who tuned in to hear a Christmas Eve rendition of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol were shocked when they heard what appeared to be a newscast from the north pole, reporting that Santa’s Workshop had been overrun in a blitzkrieg by Finnish proxies of the Nazi German government. The newscast, a hoax created by 20-something wunderkind Orson Wells as a seasonal allegory about the spread of Fascism in Europe, was so successful that few listeners stayed to listen until the end, when St. Nick emerged from the smoking ruins of his workshop to deliver a rousing call to action against the authoritarian tide and to urge peace on Earth, good will toward men and expound on the joys of a hot cup of Mercury Theater of Air’s sponsor Campbell’s soup. Instead, tens of thousands of New York City children mobbed the Macy’s Department Store on 34 In this hour-long radio drama, Santa struggles with the increasing demands of providing gifts for millions of spoiled, ungrateful brats across the world, until a single elf, in the engineering department of his workshop, convinces Santa to go on strike. The special ends with the entropic collapse of the civilization of takers and the spectacle of children trudging across the bitterly cold, dark tundra to offer Santa cash for his services, acknowledging at last that his genius makes the gifts — and therefore Christmas — possible. Prior to broadcast, Mutual Broadcast System executives raised objections to the radio play, noting that 56 minutes of the hour-long broadcast went to a philosophical manifesto by the elf and of the four remaining minutes, three went to a love scene between Santa and the cold, practical Mrs. Claus that was rendered into radio through the use of grunts and the shattering of several dozen whiskey tumblers. In later letters, Rand sneeringly described these executives as “anti-life.”

In this hour-long radio drama, Santa struggles with the increasing demands of providing gifts for millions of spoiled, ungrateful brats across the world, until a single elf, in the engineering department of his workshop, convinces Santa to go on strike. The special ends with the entropic collapse of the civilization of takers and the spectacle of children trudging across the bitterly cold, dark tundra to offer Santa cash for his services, acknowledging at last that his genius makes the gifts — and therefore Christmas — possible. Prior to broadcast, Mutual Broadcast System executives raised objections to the radio play, noting that 56 minutes of the hour-long broadcast went to a philosophical manifesto by the elf and of the four remaining minutes, three went to a love scene between Santa and the cold, practical Mrs. Claus that was rendered into radio through the use of grunts and the shattering of several dozen whiskey tumblers. In later letters, Rand sneeringly described these executives as “anti-life.” Mr. Spock, with his pointy ears, is hailed as a messiah on a wintry world where elves toil for a mysterious master, revealed to be Santa just prior to the first commercial break. Santa, enraged, kills Ensign Jones and attacks the Enterprise in his sleigh. As

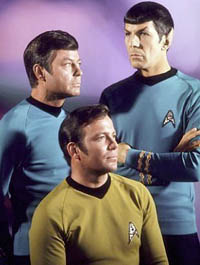

Mr. Spock, with his pointy ears, is hailed as a messiah on a wintry world where elves toil for a mysterious master, revealed to be Santa just prior to the first commercial break. Santa, enraged, kills Ensign Jones and attacks the Enterprise in his sleigh. As  This ABC Christmas special featured Santa as a happy-go-lucky swinger who comically wades into the marital bed of two neurotic 70s couples, and also the music of the Carpenters. It was screened for television critics but shelved by the network when the critics, assembled at ABC’s New York offices, rose as one to strangle the producers at the post-viewing interview. Joel

This ABC Christmas special featured Santa as a happy-go-lucky swinger who comically wades into the marital bed of two neurotic 70s couples, and also the music of the Carpenters. It was screened for television critics but shelved by the network when the critics, assembled at ABC’s New York offices, rose as one to strangle the producers at the post-viewing interview. Joel  A year before their rather more successful Christmas pairing with John Denver, the

A year before their rather more successful Christmas pairing with John Denver, the  Undeterred by the miserable flop of the movie Can’t Stop the Music!, last place television network NBC aired this special, in which music group the Village People mobilize to save Christmas after Santa Claus (Paul Lynde) experiences a hernia. Thus follows several musical sequences — on ice! — where the Village People move Santa’s Workshop to Christopher Street, enlist their friends to become elves with an adapted version of their hit “In The Navy,” and draft film co-star Bruce Jenner to become the new Santa in a sequence which involves stripping the 1976 gold medal decathlon winner to his shorts, shaving and oiling his chest, and outfitting him in fur-trimmed red briefs and crimson leathers to a disco version of “Come O Ye Faithful.” Peggy Fleming, Shields and

Undeterred by the miserable flop of the movie Can’t Stop the Music!, last place television network NBC aired this special, in which music group the Village People mobilize to save Christmas after Santa Claus (Paul Lynde) experiences a hernia. Thus follows several musical sequences — on ice! — where the Village People move Santa’s Workshop to Christopher Street, enlist their friends to become elves with an adapted version of their hit “In The Navy,” and draft film co-star Bruce Jenner to become the new Santa in a sequence which involves stripping the 1976 gold medal decathlon winner to his shorts, shaving and oiling his chest, and outfitting him in fur-trimmed red briefs and crimson leathers to a disco version of “Come O Ye Faithful.” Peggy Fleming, Shields and  Faced with Canadian content requirements but no new programming, the Canadian Broadcasting Company turned to Canadian director David

Faced with Canadian content requirements but no new programming, the Canadian Broadcasting Company turned to Canadian director David  This PBS/

This PBS/