[Cross-posted to Front Porch Republic]

[Cross-posted to Front Porch Republic]

Last week the United States went through another one of our regular, mostly ritualized exercises in mass democracy. What did (or should) localists think of it all? I don't simply mean those who, wonderfully, maintain a robust connection to their local community and at least some degree of involvement in local affairs; I mean those who do all that and who intellectually situate their local action within a broader political or social scheme. So, in other words--what did philosophical localists think of the 2018 midterm elections, or any elections in our kludgey mass democracy, for that matter? Is there a localist opinion about democracy at all? And if so, what is it?

I find myself thinking about this particularly because of the Front Porch Republic conference I attended a month and a half ago. The focus of the conference was the legacy of 1968, that monumental year a half-century ago. There were multiple excellent presentations--both funny and thoughtful--given there about the nature and consequences of the changes and crises which that year visited upon the United States. And yet, through it all, through discussions of race and gender and politics and war, I felt there was something missing. The formidable Bill Kauffman articulated it for me, though only indirectly, by way of a brief snark about Tom Hayden during his presentation. An entire day of talking about 1968, with almost no mention of all the democratic activism, party controversies, and electoral anger which shaped the civic atmosphere within which the dramatic events of that year played out, and with only one joking reference to the famed author of the Port Huron Statement (or, if you prefer, the "compromised second draft"), one of the essential texts of 1960s student radicalism and participatory democracy, to boot? That seemed...odd. Race riots, the evolution of the welfare state, clashes between police and demonstrators, assassinations, changes in sexual habits, reflections on the Vietnam War--localists can say something about, and learn something about, all of those, as the conference amply demonstrated. But can they--can we, since I was right there, with my own localist sympathies on display--say something, and learn something, about democracy itself?

The key problem, obviously, is what is meant by "democracy." Search for that word on the Front Porch Republic website, and you'll get links to dozens of articles, going back many years, consisting of dozens of different takes on dozens of different aspects of the idea. So looking for some clarity is imperative.

Localism in the Mass Age: A Front Porch Republic Manifesto is a wonderful collection, though (appropriately enough!) it has some real limits as far as the "manifesto" part of its title goes. Pick up this terrific collection of essays, and you'll find multiple beautiful, insightful, challenging snapshots, taken from a localist perspective, of our present condition. But only a few of those snapshots include any comment at all about "democracy" as either a governing system or a political ideal, and only one--Jeff Polet's excellent "Federalism, Anti-Federalism, and the View from the Front Porch"--provides any real analysis. Polet's basic perspective, and it's one that appears shared by most of the other scattered comments in the book, is resolutely Tocquevillian: that is, it expresses the fear that democracy--government by the people--cannot, in itself, provide much by way of resistance to homogenizing economies and centralizing governments which would undermine the practices upon which democratic self-government depends. Democracy alone, the argument goes, provides no resistance to people thinking about their condition individualistically and materialistically, such thinking invariably invites market economies--and market regulations--which undermine real democratic premises.

Localism in the Mass Age: A Front Porch Republic Manifesto is a wonderful collection, though (appropriately enough!) it has some real limits as far as the "manifesto" part of its title goes. Pick up this terrific collection of essays, and you'll find multiple beautiful, insightful, challenging snapshots, taken from a localist perspective, of our present condition. But only a few of those snapshots include any comment at all about "democracy" as either a governing system or a political ideal, and only one--Jeff Polet's excellent "Federalism, Anti-Federalism, and the View from the Front Porch"--provides any real analysis. Polet's basic perspective, and it's one that appears shared by most of the other scattered comments in the book, is resolutely Tocquevillian: that is, it expresses the fear that democracy--government by the people--cannot, in itself, provide much by way of resistance to homogenizing economies and centralizing governments which would undermine the practices upon which democratic self-government depends. Democracy alone, the argument goes, provides no resistance to people thinking about their condition individualistically and materialistically, such thinking invariably invites market economies--and market regulations--which undermine real democratic premises.

In the U.S., Polet sees as having developed under the reign of what he calls "egalitarian democracy," which in his view presumes a system of government that takes boundless individual equality as its starting point. From that beginning, as Tocqueville argued, individual comparisons to and resentments towards others are enabled, leading to the drive felt by most individuals to forever improve themselves, which in turn leads to endless demands for economic growth and (eventually) regulatory expansion, both of which undermine "the preservation of individuals in their self-sufficient liberty" (pp. 54-55). The democratic impulse, then, at least when not constrained and contextualized by being "enmeshed in distinctive local communities," will only encourage retreat from the social sphere, eroding "our capacity to love what is nearest and most particular," and creating "disconnected citizens who relate primarily by means of tolerance or cash relations" (pp. 55-56). Sadly, the massive, intricate, yet also crudely partisan and more often than not thoroughly nationalized political debates of the just-completed midterm elections don't immediately suggest any reason for localists to dissent from Polet's diagnosis.

Polet's Tocquevillian analysis is reflected, and refined, within the new book by Patrick Deneen (one of the founding fathers of Front Porch Republic), Why Liberalism Failed. Deneen's sometimes superb (because of its smart, carefully written synthesis of so many anti-liberal arguments) and sometimes frustrating (because that synthesis is too often simplistic and incomplete) book makes the claim that the localist concern with democracy expressed by Polet and others is, in his view at least, best expressed as a concern with liberal democracy. As he put it:

Polet's Tocquevillian analysis is reflected, and refined, within the new book by Patrick Deneen (one of the founding fathers of Front Porch Republic), Why Liberalism Failed. Deneen's sometimes superb (because of its smart, carefully written synthesis of so many anti-liberal arguments) and sometimes frustrating (because that synthesis is too often simplistic and incomplete) book makes the claim that the localist concern with democracy expressed by Polet and others is, in his view at least, best expressed as a concern with liberal democracy. As he put it:

Liberalism...adjectively coexists with the noun "democracy," apparently giving pride of place to the more ancient regime form in which the people rule. However, the oft-used phrase achieves something rather different from its apparent meaning: the adjective not only modifies 'democracy' but proposes a redefinition of the ancient regime into its effective opposite, to one in which the people do not rule but are instead satisfied with the material and martial benefits of living in a liberal res idiotica....[T]he true genius of liberalism was to subtly but persistently shape and educate the citizenry to equate "democracy" with the ideal of self-made and self-making individuals...while accepting the patina of political democracy shrouding a powerful and distant government whose deeper legitimacy arises from enlarging the opportunities and experience of expressive individualism. As long as liberal democracy expands the "empire of liberty," mainly in the form of expansive rights, power, and wealth, the actual absence of active democratic self-rule is not only acceptable but a desired end" (pp. 154-155).

There are several interesting implications here, perhaps the most important of which is that localists presumably ought to have an affection for that "ancient," more communitarian or republican forms of democracy which are "illiberal," as Deneen puts it elsewhere in his book. Relying on Tocqueville yet again, Deneen locates "democracy properly understood" with the Puritans, and their legacy of small, mostly homogeneous, religiously oriented towns practicing direct, collective self-rule. "Democracy required the abridgment of the desires and preferences of the individual, particularly in light of an awareness of a common good that could become discernible only through ongoing interactions with fellow citizens...Democracy, in [Tocqueville's] view, was defined not by rights to voting either exercised or eschewed but by the ongoing discussion and disputation and practices of self-rule in particular places over a long period of time" (pp. 175-176). People who have been shaped by and/or long for the virtues of localism ought to want to be part of the maintenance and governance of such; hence, local democracy ought to be a goal, and localists ought not be deluded into thinking that the expansive (and therefore often alienating) operations of contemporary mass, electoral, liberal democracy can do the trick.

But is that an argument to refuse to participate in the democratic system America currently has? Or a call for localists to engage in it, and by so doing strive to reform and re-vivify it? Deneen, unfortunately, basically passes over the whole range of historical and philosophical arguments dealing with populist or participatory democracy. He does acknowledge that "progressive liberals" have, over the past 100 years, taken many steps which have enabled "more direct forms of democratic governance," but since those same reforms have been attended by a professionalization of the policy-making process, he thinks the result has actually been a limiting of democracy to "the expression of preferences," which, unlike actual, practical governing work, can be easily abstracted, commodified, and marketed to (pp. 159-160). The fear that democratic reforms aiming at increasing participation only end up increasing the influence of elite experts is, admittedly, one reason to be suspicious of any talk about civic empowerment which doesn't involve a wholesale rejection of liberalism. And yet, it's hardly the case that "elites" are absent from "ancient" or "illiberal" forms of democracy either. On the contrary, they are recognized explicitly as playing a needed role. Polet writes that the corruption of American democracy could only have happened once "authority was dislocated" in "religion, economics, family life [and] local life" (p, 58) and Deneen worries that always working to forestall "local autocracies or theocracies" in the name of freedom and equality only extends an anti-democratic "liberal hegemony" (pp. 196-197). So what, exactly, are the sorts of elites which philosophical localists who 1) hope to preserve democracy without 2) dismissing everything liberalism and egalitarianism have accomplished (accomplishments that Deneed, Polet, and every other serious localist can't pretend to ignore) need be most afraid of?

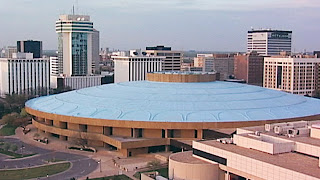

Perhaps the elites in question are those connected with cities and the powerful financial and cultural forces which such urban spaces both cultivate and presume? That may seen like a rather peculiar leap, but it is a connection which, once again, Tocqueville explicitly puts on the table: as Polet argues (p. 56), and Deneen and other localists concur, for Tocqueville the great sign of the degeneration of democracy is the rise of "capital cities," metropolises of significant size, all of which are able to command economic and social resources that exacerbate the always-lurking aspirations and resentments of self-interested individuals. To quote the man himself: "In cities men cannot be prevented from concerting together, and from awakening a mutual excitement which prompts sudden and passionate resolutions....To subject the provinces to the metropolis is therefore not only to place the destiny of the empire in the hands of a portion of the community...but to place it in the hands of a populace acting under its own impulses, which must be avoided as dangerous" (Democracy in America, Part 1, Chp. 17).

The key passage there, I think, at least in reference to what seems common among all these localist defenses of "ancient" or "illiberal" democracy, is that the population of cities is "acting under its own impulses"--in contrast, in presumably, to those in smaller communities, whose passions are still subject to community expectations, local traditions, and family roles. Of course, to enjoy the ability to act under one's own impulses has been the attraction of cities for hundreds of millions for thousands of years--the legendary 13th-century German peasant who claimed "Die Stadtluft macht frei!" wasn't a creature shaped by the acquisitiveness and envies of modern market economies, that's for certain. But the fact that cities have always played a central role--whether enriching, parasitic, or both--in our socio-economic and socio-political contexts is hardly an argument against thinking about their democratic costs and consequences. The Republican voters here in very Republican Kansas who, in the wake of an election which put Democrat Laura Kelly in the governor's mansion, look at the election map, note the nine urban (or more urban than their neighbors) counties that gave her a winning plurality, and start muttering about the need for an electoral college for the our state, can perhaps be forgiven, even if they're wrong.

The key passage there, I think, at least in reference to what seems common among all these localist defenses of "ancient" or "illiberal" democracy, is that the population of cities is "acting under its own impulses"--in contrast, in presumably, to those in smaller communities, whose passions are still subject to community expectations, local traditions, and family roles. Of course, to enjoy the ability to act under one's own impulses has been the attraction of cities for hundreds of millions for thousands of years--the legendary 13th-century German peasant who claimed "Die Stadtluft macht frei!" wasn't a creature shaped by the acquisitiveness and envies of modern market economies, that's for certain. But the fact that cities have always played a central role--whether enriching, parasitic, or both--in our socio-economic and socio-political contexts is hardly an argument against thinking about their democratic costs and consequences. The Republican voters here in very Republican Kansas who, in the wake of an election which put Democrat Laura Kelly in the governor's mansion, look at the election map, note the nine urban (or more urban than their neighbors) counties that gave her a winning plurality, and start muttering about the need for an electoral college for the our state, can perhaps be forgiven, even if they're wrong.

Why am I confident they're wrong? Because there is a reason the peasants (and the people of Trego, Labette, Nemaha, Hamilton, and 92 other rural counties here in Kansas) fled to the local walled city (and to the cities of Sedgwick, Johnson, Douglas, and about six other more urbanized counties in our state), and that reason was, for the most part, entirely unobjectionable, politically speaking. It was, of course, about going to where the economic opportunities are. Unless you simply reject out of hand the very notion of respecting the reasons human beings actually give for their own actions, then the fear of urban temptations systematically poisoning local norms and perspectives has to be accepted as a fiction. That's not to say that there aren't a host of other variables are at work in the matter of urbanization, many of which deserve serious structural critique. But it is, I think, simply wrong to ignore that--to quote John Médaille from his mostly sympathetic FPR review of Deneen's book--while politics may be downstream from culture, culture, itself, is "downstream from breakfast." People need satisfying work, and such work is, tragically, often hard to find outside of cities. If the localist argument for democracy necessitates a push against the dominance of cities, the target should not be the disempowering of urban voters, but rather the disempowering of the global capitalism which rewards financial centers, rather than once-productive farming towns, with the wealth from which economic opportunities are made. (As Médaille also smartly observed, "subsidiarity works two ways"--localists need to attend to the "higher level formations" that allow "the household economy" to flourish in the first place.)

As I noted, none of this is a reason for localists, particularly those wanting to hold onto the pursuit of the virtues of self-government, to become unconcerned boosters of urbanism. One of Deneen's teachers, the famed political theorist Benjamin Barber, became such a booster towards the end of his life, and while his final books (If Mayors Ruled the World and Cool Cities) make some important and challenging arguments about urban sovereignty, environmental politics, and the enduring questions of democratic legitimacy, the romance of "global capital flows," "nodes of cultural transmission," and much more cosmopolitan cant got in the way of a genuinely serious consideration of the social (and, perhaps, democratic) costs of urbanism to Barber's republicanism. Deneen wrote a wonderful survey of Barber's career ("How Swiss Is Ben Barber?" in Strong Democracy in Crisis [2016]) which carefully, and somewhat regretfully, charted Barber's move from his original description and defense of the "local, direct forms of democracy" found in the "pastoral, non-commercial, 'parochial'" cantons of Switzerland in the 1960s, to his articular of "strong democracy" in light of "the unavoidable reality of modernization, capitalism, liberalism, and the nation-state," and finally to his claimed "return to the local," with his emphasis upon urban democracy...though, tellingly, mostly just the democratic potential of elite networks tying together the great, global cities of the world (since they have are characterized by both a sufficiently cosmopolitan population and a sufficiently command over financial resources to supposedly be able to put forward democratically sustainable and actually effective climate change-fighting policies). Deneen succinctly puts forward the fundamental problem here:

As I noted, none of this is a reason for localists, particularly those wanting to hold onto the pursuit of the virtues of self-government, to become unconcerned boosters of urbanism. One of Deneen's teachers, the famed political theorist Benjamin Barber, became such a booster towards the end of his life, and while his final books (If Mayors Ruled the World and Cool Cities) make some important and challenging arguments about urban sovereignty, environmental politics, and the enduring questions of democratic legitimacy, the romance of "global capital flows," "nodes of cultural transmission," and much more cosmopolitan cant got in the way of a genuinely serious consideration of the social (and, perhaps, democratic) costs of urbanism to Barber's republicanism. Deneen wrote a wonderful survey of Barber's career ("How Swiss Is Ben Barber?" in Strong Democracy in Crisis [2016]) which carefully, and somewhat regretfully, charted Barber's move from his original description and defense of the "local, direct forms of democracy" found in the "pastoral, non-commercial, 'parochial'" cantons of Switzerland in the 1960s, to his articular of "strong democracy" in light of "the unavoidable reality of modernization, capitalism, liberalism, and the nation-state," and finally to his claimed "return to the local," with his emphasis upon urban democracy...though, tellingly, mostly just the democratic potential of elite networks tying together the great, global cities of the world (since they have are characterized by both a sufficiently cosmopolitan population and a sufficiently command over financial resources to supposedly be able to put forward democratically sustainable and actually effective climate change-fighting policies). Deneen succinctly puts forward the fundamental problem here:

Even as [Barber] commends cities as "natural venues for citizen participation," he does not dwell on the relative civic disconnection that not only is a signal feature of many...of the world's cities...but may in fact constitute one of the main attractions for urban dwellers: that is, relative anonymity, "loose connections," and an engrossing concern for private and commercial opportunities....Barber's latest book represents...a "return" to his earliest concerns that link democracy with a strong local connection...but having "translated" that concern in the context of the modern, commercial, cosmopolitan city, it is not clear that he has similarly "translated" the likelihood of democratic flourishing in such a double-edged locus (pp. 109-110).

The doubled-locus in question is one that any localist who values democracy but also values liberal capitalism (or at least does not want to see it abruptly and arbitrarily overthrown) has to struggle with. Urbanites (which is, of course, close to 80% of us in the United States, and over half the planet's population overall) need to be able to, and should be able to seek to, exercise the same opportunities for self-government that all localists hold dear, but that runs against the general anonymity, the disconnected elites, and the abstract, non-embedded cultural priorities which large and diverse cities appear to promote and, to a degree, depend upon. Cities are not, I think, best understood as partaking in some kind of structurally anti-Tocquevillian conspiracy against the possibility of more communitarian forms of democracy, but nonetheless cities are profoundly, even constitutively, liberal in their functioning. And even if that philosophical liberalism doesn't always translate into voting for self-described "liberal" or "progressive" candidates and causes, it does often enough that the divide between the majority of urban voters and the majority of rural voters was one of the clearest and starkest results of the 2018 midterm elections, and not just here in Kansas.

The best research confirms the basic localist suspicion that "people in larger cities are much less likely to contact officials, attend community or organizational meetings...vote in local elections...or be recruited for political activity by neighbors, and are less interested in local affairs." They are not, in short, as consistent incubators of democratic habits as smaller towns may be--very possibly because of all the aforementioned Tocquevillian reasons, especially the depressing dominance of urban politics by deracinated, disconnected elites. But to call for federal and exclusionary structures that would block urban populations from exercising their democratic demands for fair representation is shows, I think, perversely too much attachment to electoral politics in a liberal society. Specifically, instead of thinking about how to change, re-arrange, and therefore renew democratic possibilities within our polities, it reveals a desire to thrust any and all perceived threats to their already-problematic status quo outside of them. (Thankfully, urban voters here in Kansas were essential to defeating a gubernatorial candidate who had built much of his career around attempting just that.) It may well be that the participatory ideas of democratic activists like Hayden never really truly engaged with the way cities can change, and thus quite possibly warp and undermine (or perhaps occasionally even enrich?), democracy; he was once quoted in The New York Times as saying that ending "the alienation from government that is so prevalent in society today...the answer is not busting up a big city into a lot of small cities," and one would hope that, were he alive today, he'd be willing to at least entertain that possibility. But whatever the limitations of democratic activism, their ideas need to be wrestled with by philosophical republicans and localists like Polet and Deneen, confronted as they are by the reality of liberal democracy, with all its flaws, in America today.

In parting, one example of such intellectual engagement: Susannah Black's essay "Port City Confidential," one of the most lyrical and thoughtful contributions in Localism in the Mass Age. Black confronts the problem which cities pose for conservatism--and, by a not-too-strained extension (or so I would argue), the problem they pose for any communitarian, republican, or illiberal articulations of democracy as well. To not figure out how to democratically accept the city--and the kinds of practical education in limits and community connection and place with they provide, to at least some urbanites, in some contexts, some of the time--is to allow one's "hunger for stability" to associate stability solely with "the quasi-mythical stable communities of the past," rather than recognizing that urban life incorporates, instead of an illusionary stability, the higher "New Jerusalem" ideal of "a multiethnic exuberant rejection of all apartheid, a city full of people from all the nations" (p. 217). That sounds very cosmopolitan--but the hope for localists, especially in our 21st-century liberal capitalist world, must be that there remains (via one kind of philosophical or political formulation or another) an actual polis within our globalized, urbanized cosmopolis. Perhaps Barber was not entirely wrong to gesture in that direction--at the very least, the liberal voters and (hopefully) aspiring democratic activists of today's cities might be able to make a better accounting of themselves as part of interdependent, aspirational networks, local and regional and otherwise, rather than as mere contestants for control over the modern liberal state.

In parting, one example of such intellectual engagement: Susannah Black's essay "Port City Confidential," one of the most lyrical and thoughtful contributions in Localism in the Mass Age. Black confronts the problem which cities pose for conservatism--and, by a not-too-strained extension (or so I would argue), the problem they pose for any communitarian, republican, or illiberal articulations of democracy as well. To not figure out how to democratically accept the city--and the kinds of practical education in limits and community connection and place with they provide, to at least some urbanites, in some contexts, some of the time--is to allow one's "hunger for stability" to associate stability solely with "the quasi-mythical stable communities of the past," rather than recognizing that urban life incorporates, instead of an illusionary stability, the higher "New Jerusalem" ideal of "a multiethnic exuberant rejection of all apartheid, a city full of people from all the nations" (p. 217). That sounds very cosmopolitan--but the hope for localists, especially in our 21st-century liberal capitalist world, must be that there remains (via one kind of philosophical or political formulation or another) an actual polis within our globalized, urbanized cosmopolis. Perhaps Barber was not entirely wrong to gesture in that direction--at the very least, the liberal voters and (hopefully) aspiring democratic activists of today's cities might be able to make a better accounting of themselves as part of interdependent, aspirational networks, local and regional and otherwise, rather than as mere contestants for control over the modern liberal state.

Many Kansas Republicans likely guffawed in disbelief when Governor Laura Kelly recently

insisted "I am a major local-control advocate" and that she was opposed to "usurping" the power of local governments. The stereotype of Democrats as always favoring

centralized government programs, with Republicans always fighting to keep government

small and local, is deeply entrenched in our national political discourse, and it's an image which the Kansas Republican party fully intends to make use of this election year. The language of the state GOP, which dominated much of the spring legislative special session, presents Kelly’s emergency orders during

the pandemic as examples of one-size-fits-all overreach, thus building on this stereotype expertly.

Many Kansas Republicans likely guffawed in disbelief when Governor Laura Kelly recently

insisted "I am a major local-control advocate" and that she was opposed to "usurping" the power of local governments. The stereotype of Democrats as always favoring

centralized government programs, with Republicans always fighting to keep government

small and local, is deeply entrenched in our national political discourse, and it's an image which the Kansas Republican party fully intends to make use of this election year. The language of the state GOP, which dominated much of the spring legislative special session, presents Kelly’s emergency orders during

the pandemic as examples of one-size-fits-all overreach, thus building on this stereotype expertly.