[A version of this piece is cross-posted to Current]

How might one politically categorize the following statement?

[M]y

apparently disparate-sounding worries....all result from one or another move on

the part of the culture away from the immediate, the instinctual, the

face-to-face. We are embodied beings, gradually adapted over millions of year

to thrive on a certain scale, our metabolisms a delicate orchestration of

innumerable biological and geophysical rhythms. The culture of modernity has

thrust upon us, sometimes with traumatic abruptness, experiences,

relationships, and powers for which we may not yet be ready–to which we may

need more time to adapt....If we cannot slow down and grow cautiously, evenly,

gradually into our new technological and political possibilities and

responsibilities–even the potentially liberating ones–the last recognizably

individual men and women may give place, before too many generations, to the

simultaneously sub- and super-human civilization of the hive.

For those whose

exposure to or engagement with political ideas is fairly minimal–whether by

choice or by circumstance or both–the question would likely seem strange. After

all, there are no obvious partisan markers anywhere in this statement, no

references to presidential candidates or global events or policy disputes. So

what is political about it? But for those who have some familiarity with the

history of political ideas and arguments, as well as some of their attendant

philosophical formulations and literary tropes, there are flags in this

statement which suggest an answer–and that answer, in all likelihood, would be

“conservative.”

Not

“conservative” in the way most Americans would be likely to use the term today,

to be sure. The passage doesn’t provide anything that connects to Donald Trump

or lower taxes or tighter immigration or anti-LGBTQ positions or the Supreme

Court, at least not directly. But astute readers would pick up on the final

sentence’s reference to Friedrich Nietzsche’s “last man,” his vision of a

humanity that has succumbed to nihilism, hedonism, and passivity, and thus

falls into a kind of groupthink where all individual accomplishments are lost.

The passage also speaks warningly about developments and innovations of

modernity which humanity, whose embodiment reflects a deep evolutionary

grounding in small-scale interactions, needs to be far more cautious about embracing.

Hence, the politics of this passage could be–and, I think, would be, if read

without any additional context–plausibly coded as small-c conservative, or at

least as philosophically anti-progressive. Its implications include a

preference for the local, a suspicion of intellectual abstractions, a

discontent with the ennui that consumer wealth and technological ease has

enabled, and a fear of a too-rapidly pursued future whose liberating

possibilities will likely be lost unless they are approached incrementally (if

at all). In short, it communicates a respect for, even a valuation of, a more

limited conceptualization of our social world–and, aside from certain strains

of environmental concern within the current constellation of liberal thought,

talk of “limits” is generally seen as the provenance of conservatives, not

progressives.

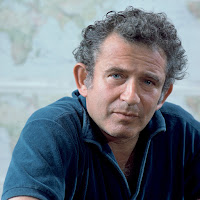

And yet, the

author of this passage is George Scialabba, a man of–as was once not

infrequently said of writers like him–“the left.” Scialabba is a highly

regarded essayist, book review, and public intellectual, whose latest

collection, Only a Voice:

Essays (Verso, 2023), is a brilliant collection of insightful readings

and contrarian arguments about some of the most important thinkers and writers

of the past century, and some from centuries earlier: Adam Smith, Thomas Paine,

T.S. Eliot, Leo Strauss, Irving Howe, I.F. Stone, and many more. The essay

“Last Men and Women,” a survey of criticisms of mass society and modern

democracy, includes the passage quoted at the beginning of this essay, but also

this plain self-description: “[This]...is where I also stand–with the

Enlightenment and its contemporary heirs, and against Straussians, religious

conservatives, national greatness neoconservatives, Ayn Randian libertarians,

and anyone else for whom tolerance, civic equality, international law, and a

universal minimum standard of material welfare are less than fundamental

commitments.” Whatever else might be said about that self-description (which

was published in 2021), it doesn’t sound at all “conservative,” even in the

small-c sense. So should we conclude therefore that Scialabba is simply

inconsistent? Or might there be a political categorization which can, in a

theoretically consistent way, capture both his progressive Enlightenment

aspirations, and well as his worries about the same?

And yet, the

author of this passage is George Scialabba, a man of–as was once not

infrequently said of writers like him–“the left.” Scialabba is a highly

regarded essayist, book review, and public intellectual, whose latest

collection, Only a Voice:

Essays (Verso, 2023), is a brilliant collection of insightful readings

and contrarian arguments about some of the most important thinkers and writers

of the past century, and some from centuries earlier: Adam Smith, Thomas Paine,

T.S. Eliot, Leo Strauss, Irving Howe, I.F. Stone, and many more. The essay

“Last Men and Women,” a survey of criticisms of mass society and modern

democracy, includes the passage quoted at the beginning of this essay, but also

this plain self-description: “[This]...is where I also stand–with the

Enlightenment and its contemporary heirs, and against Straussians, religious

conservatives, national greatness neoconservatives, Ayn Randian libertarians,

and anyone else for whom tolerance, civic equality, international law, and a

universal minimum standard of material welfare are less than fundamental

commitments.” Whatever else might be said about that self-description (which

was published in 2021), it doesn’t sound at all “conservative,” even in the

small-c sense. So should we conclude therefore that Scialabba is simply

inconsistent? Or might there be a political categorization which can, in a

theoretically consistent way, capture both his progressive Enlightenment

aspirations, and well as his worries about the same?

I think there

is–though, as with all ideological labels, it’s a categorization with greater

use as a conversational reference than as an analytical tool. The label is

“left conservatism,” and applying it to Scialabba’s writings–or, perhaps more

accurately, using Scilabba’s writings to apply the label more broadly–is an

intellectual exercise worth engaging in, especially in our moment when so many

other political categorizations seem either overthrown or irrelevant or both.

The

term “left conservative” is hardly new; it’s been coined and re-coined multiple

times over the decades. Most recently, the term been revived in some conservative

publications

to describe a mix of anti-globalist, socially conservative, pro-labor, subsidiarian

perspectives which recognize the need for protectionist action to strengthen

national economies and local cultures. Those considerations are accurate, so

far as they go. But to really dig into the idea–and to assess its fit with

Scialabba’s incisive considerations of our moment–we need to look to an earlier

expression of it, one found in the third-person self-description Norman Mailer

provided in his book Armies of the Night:

“Mailer was a Left Conservative. So he had his own point of view. To himself he

would suggest that he tried to think in the style of Marx in order to attain

certain values suggested by Edmund Burke.” What is it that Mailer was

describing there, this Marxian-style attainment of Burkean principles? By “the

style of Marx” one must presumably mean employing a revolutionary, or at least

structural, set of intellectual tools, ones addressed to emancipation of

persons and goods in society; by “values suggested by Edmund Burke,” one must

presumably be talking about local communities and the traditions they give life

to, and the need to maintain and strengthen them. So how to put that together?

The

term “left conservative” is hardly new; it’s been coined and re-coined multiple

times over the decades. Most recently, the term been revived in some conservative

publications

to describe a mix of anti-globalist, socially conservative, pro-labor, subsidiarian

perspectives which recognize the need for protectionist action to strengthen

national economies and local cultures. Those considerations are accurate, so

far as they go. But to really dig into the idea–and to assess its fit with

Scialabba’s incisive considerations of our moment–we need to look to an earlier

expression of it, one found in the third-person self-description Norman Mailer

provided in his book Armies of the Night:

“Mailer was a Left Conservative. So he had his own point of view. To himself he

would suggest that he tried to think in the style of Marx in order to attain

certain values suggested by Edmund Burke.” What is it that Mailer was

describing there, this Marxian-style attainment of Burkean principles? By “the

style of Marx” one must presumably mean employing a revolutionary, or at least

structural, set of intellectual tools, ones addressed to emancipation of

persons and goods in society; by “values suggested by Edmund Burke,” one must

presumably be talking about local communities and the traditions they give life

to, and the need to maintain and strengthen them. So how to put that together?

The most

intellectual plausible articulation of this idea, I think, is to say that

modernity–whether that is dated to the Protestant Reformation, the Declaration

of Independence, the Industrial Revolution, or any other particular historical

landmark or era–is simply different from what came before it. The 18th-century

(and earlier) traditions and communities which Burke defended cannot exercise

the authority they once did in a world in which individual subjectivity has

conditioned our very understanding of the self. Technology, social fluidity,

capitalism, democracy: all are genies let out of the bottle, in the face of

which traditions of all kinds suffer. (Marx’s famous statement in The Communist Manifesto that, with

industrialization, “all-fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of

ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions are swept away....all that is

solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned,” is an obvious support to

this formulation, but Scialabba himself adds one as well, describing Burke’s own

writings as “expressions of outraged common sense” in the face of the

inevitable—and, he asserts, entirely justified—transformations that came with

the expansion of suffrage and other “democratic truths”). Hence, the

preservation of Burkean values–acting “conservatively,” in other words--now

requires actions which go beyond the expansion of liberal guarantees or the

amelioration of socio-economic disruptions.

This reading of Mailer may simply sound like the conservative insight famously expressed by G.K. Chesterton in his book Orthodoxy: “If you leave a white post alone it will soon be a black post. If you particularly want it to be white you must be always painting it again; that is, you must be always having a revolution.” But the “revolution” invoked by Chesterton in the name of conserving a particular state of affairs was a formal, not structural one, whereas the better understanding of Mailer’s point about “think[ing] in the style of Marx,” I believe, means something truly “left”in the structural, even radical, sense. Maybe, the left conservative thinks, only a radical shift towards the democratization, the socialization, and the equalization of the products and processes of modernity will be sufficient to enable people to continue to thrive in their communities.

And it really

is communities which are central here. (One could argue that “left

conservatism” might better be expressed as “left communitarianism,” and there’s

some value to putting it that way. But since the connections and commonalities

which emerge in the context of communities are, I think, something that human

beings, as political animals, always seek to construct and always mourn the

absence of–and here I am heavily influenced by the writings of Michael Walzer and Charles Taylor, two political

philosophers that were frequently labeled “communitarians” when that

term enjoyed a boomlet 30 years ago–focusing on the concern to literally conserve

that which is genuinely valuable about our communities is appropriate.) Our

individualistic age puts an asterisk of suspicion beside all communities,

however defined, seeing them all as potential sources of majoritarian abuse or

undemocratic tyranny–which, of course, they too often are; as Christians at

least ought to be quick to acknowledge, we are fallen beings, after all. But

the conservative desire for belonging and rootedness and community, whatever

evils it enables, also grounds both democratic and egalitarian possibilities:

traditions are forms of meaning and fulfillment which cannot (or at least

cannot easily) be turned into abstractions and thus be taxed away from you or

turned against you by those who wield power. To the extent that the modern

world sees profits, procreation, wars, borders, religions, holidays, families,

markets, marriages, and more as institutions and events best understood,

conducted, and transformed in light of some abstract principle--whether that be

individual rights or personal conscience or democratic harmony or economic

progress--one could argue, if one is of this particular conservative

orientation (as I think Scialabba is, at least partly), that something in the

modern world has gone wrong, or at least has gotten too far away from the

instinctual truths and embedded necessities of human existence, truths and

necessities which are the necessary (if not sufficient) prerequisites to treating

all people as equally capable of self-rule and equally deserving of respect.

That’s not necessarily a defense of all communities, especially not national

ones, which too regularly employ the coercive power of the state to maintain

the definition and borders which those in power decide upon; Mailer’s

communitarianism, a term he probably would have blanched at, was decidedly small-scale

and anarchic. But the centrality of being in connection with others, and

defending those connections, remains.

Not many have

picked up on this reading of Mailer’s ideas in the two generations since, to

say the least. On the left or progressive liberal side of America’s

intellectual divide, as it began to deepen and sharpen in the decades following

the upheavals of the 1960s, leftism mostly focused its decreasing energies on

various statist parties and platforms, while most liberals came to treat those

who worried about the excesses of their individualistic liberatory language as

either 1) accidental intellectual traitors (as it was frequently expressed at a

UC-Santa

Cruz conference on the “specter of left

conservatism” in 1998, these unfortunate folk are genuine leftists whose

distaste for the latest theoretical developments has tricked them into allying

with conservative forces), or 2) just remnants of an old rural conservative

Democrat faction, soon to die out. That’s assuming White voters were the ones

being discussed, of course; the religiousity and social conservatism of many

Black voters was treated very differently, though not until Bill Clinton was its

preferred language given much credence, and even that didn’t last–Barak Obama,

our first Black president, reflected very little of that sensibility while in

the White House (which, cynically speaking, is perhaps one of the reasons he

was able to attain it.)

As for

America’s rightward flank, the rise of a pro-business, anti-socialist

libertarianism as a component of the Republican coalition from the 1960s

through the 1990s made any kind of liberal egalitarianism, much less leftism,

unwelcome there. Occasionally you see attempts to import into American

conservative discourse “Red Tory” formulations more common to Western European

conservatism generally, but despite gestures in that direction (George W.

Bush’s “compassionate conservatism,” for example), none of them have in any

significant way shaped the overall conservative coalition in the U.S. Of

course, some would insist upon adding a “until the rise of Donald Trump in

2016” to that sentence, and it is true that Trump’s profound lack of

ideological (much less ethical) grounding has arguably presented an opening for

leftist ideas to experience a revival in Republican circles. But while in

today’s America you are, in fact, more likely to hear talk of structural or

revolutionary changes to our liberal capitalist and democratic order coming

from the Trumpist corner of the Republican party than from the Democrats led by

Joe Biden, that talk is generally, and tragically, reflective of a

fascist-adjacent authoritarianism which too many social conservatives,

following Trump, seem to have become comfortable with. Even thoughtful

and nominally worker-friendly treatments of the integralist argument in

favor of more firmly supporting traditional community-based values seem to

presume egalitarianism itself to be the real problem, and what limited

appreciation for the solidarist approach to building economic equality–meaning

unions, mainly–which still exists in America today is found coming the

Democrats and the White House, not Mar-a-Lago.

All

of which means that the left conservative position lacks a broad constituency

in American politics. But that does not

mean it lacks a voice. Perhaps most influentially, the historian Christopher

Lasch, long a hero to many dissident and contrary conservatives (even as he

remained personally a committed Democratic voter and a firm-if-worried supporter

of the liberal egalitarian project overall through his life), and someone who

himself never used terms like “left conservative” or “communitarian” in a self-descriptive

way (even as close students of Lasch work subsequently used both),

articulated at least the outlines of what could be called a left conservative

ideology as well as anyone. And Scialabba presents, in multiple essays, Lasch

as perhaps the most valuable of all the “antiprogressives” (which is not

the same as “conservatives”) whom he holds that fans of the Enlightenment, like

himself, must learn from.

That learning,

he writes, involves grappling with the best thinkers’ “combination of

discrimination and democratic passion,” defining the latter as “the constant

remembrance that democracy entails not merely that the people should be

governed well but also that the people should govern.” Mourning the tendency of

intellectuals and politicians of all stripes–including both what he calls “the

business party” and “the Progressives”–to ignore this fundamental principle,

Scialabba’s cast of heroes includes, as he lays them out in his introduction to

Only a Voice, scholars and activists

and writers who, in one way or another, demonstrate a “moral intelligence” that

“allowed them to make relevant distinctions and get the difficult decisions

right.” This means, rather than simple apologists for the Enlightenment, such

figures as Randolph Bourne, George Orwell, Irving Howe, Barbara Ehrenreich,

Noam Chomsky, Ralph Nader, Richard Rorty, Bill McKibben, along with Lasch, earn

his praise. These are people who, in his view, take seriously their “democratic

obligation to persuade people before legislating for them”–and that means

taking seriously the “anxieties about modernity” which confront all those whom

these thinkers and writers, like Scialabba himself, attempt to clarify the

democratic options for. The responses to this anxiety which these writers all

wrestled with obviously vary greatly, from Rorty’s advocacy of setting aside

worries about “self-creation” in the name of a bland yet vital “tolerance,” to

Howe’s insistence that the ideal of socialism “will need to be reimagined in

every generation,” to, perhaps most centrally, Lasch’s populist insistence the

“the democratic character can only flourish in a society constructed to the

human scale.” Yet Scialabba thoughtfully considers–and by so doing, makes it

possible to learn from–them all.

That this

practice of thoughtful learning includes giving sympathetic attention to what

he calls “perhaps the most significant strain of social criticism in our time,”

the “antimodernist radicalism” of limits one can find in writers like D.H.

Lawrence, Lewis Mumford, Ivan Illich, Wendell Berry, or Lasch himself, is not

entirely pleasing to even some of Scialabba’s most enthusiastic readers. In a

review essay on Only a Voice in

Commonweal, Sam Adler-Bell gently suggests that Scialabba misunderstands

that modernity’s anxieties and doubts are less to be responded to than embraced

as actually one of its strengths: the modern person “is not necessarily a

conformist, a face in the crowd, incapable of independent thought,” but rather

“is someone who detects these frailties in everyone else.” This is a subtle

point, and a good one, but it also strikes me as an inverted application of

Robert Frost’s famous comment that a liberal is someone too broad-minded to

take their own side in an argument. Scialabba is far too conscientious a

thinker to deny the immense accomplishment of Enlightenment liberalism in

teaching people to be skeptical of the limits and presumptions they inherit or

which have been imposed upon them. But he also recognizes, as anyone with even

a smidgen of leftist suspicion of the bourgeoisie should, that such skepticism,

without a foundation in practices and places and, yes, even prejudices–in the

sense of “pre-judgments”–to draw upon, will often result not in robust,

democracy-defending free-thinking, but rather in a literally care-less

disconnection, a tendency to abstraction which capitalist overlords will be

more than happy to use to manipulate and oppress. As Scialabba writes in

“Progress and Prejudice,” the first and most overarching essay in Only a

Voice, he has come to recognize “with some reluctance” that thinkers like

Lasch are correct: that “as long as modernization is involuntary,” then

conserving our ability to draw upon and stay within “our own skins—and even,

perhaps, within traditional social forms” is needed, if our “every liberation”

is not to be “captured and exploited.”

Left

conservatism is one way of articulating a set of political convictions that

can, at least as a matter of theory, see this needle, the needle which

modernity has presented us with, and thread it, thus enabling the continued

project of weaving together (or sewing up tears within) our democratic

political fabric. Scialabba, through his writing over the decades, like Lasch

himself in decades prior, has been an insightful advocate for the kind of

democratic learning which all of America’s diverse communities need–a learning

which reminds us of modernity’s liberating and equalizing accomplishments, and

what must be conserved if the left’s emancipatory project is to continue.

Whether this political categorization fits him well or not, his position is one

much worth contemplating–an action which would have to begin with reading his

most recent, and excellent, book.