Defending Superman's Sentimentality

[Note: Spoilers follow.]

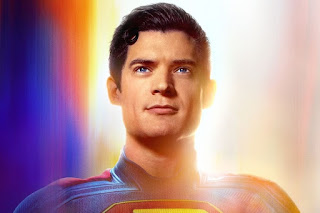

I’ve seen James Gunn’s Superman, and I’ve written up my take on it on social media: I thought it was absolutely wonderful, one of the very best super-hero movies I’ve ever seen, on the same level as—or maybe exceeding—such movies as Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man 2, Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther, Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins, Jon Favreau’s Iron Man, even Richard Donner’s Superman: The Movie. Some disagree with that assessment, which is fine; there are all sorts of ways, both stylistic and substantive, to judge big pop entertainments like these, and I’m not inclined to argue (much) with folks whose takes differ from mine.

But a politico-theological argument? That I can absolutely get into.

Given that Superman, no matter how one tells his story, is by definition a hero of the underdog, someone who saves lives, stops disasters, and fights those who oppress and terrorize, it’s always going to be easy to fit him into a particular political narrative, and certainly there’s been plenty of that in the wake of the visuals and narrative choices which Gunn employed in making Superman. (As one of my friends said regarding Vasil Ghurkos, the evil ruler of Boravia who is central to Lex Luthor’s scheme to destroy Superman, Gunn made him look like Benjamin Netanyahu, but sound like Vladimir Putin.) From what I can tell, the lazy political attack on the movie—that it’s “woke” and therefore nothing but progressive propaganda—doesn’t seem to have legs; multiple conservative, Trump-supporting friends of mine have loved the movie, loved the humor and action and heroism the film contains. Another, slightly different attack caught my eye, though, and I want to say why I think it’s completely wrong.

It's an attack made by Daniel McCarthy, the editor of Modern Age, a rather idiosyncratic conservative journal. In a column titled “What Trump Knows About ‘Superman’ That Hollywood Can’t Comprehend,” McCarthy writes that attempts to hate on Superman because of its presumed (and I think actually quite obvious and accurate) messages regarding immigration and respect for civil rights and the rule of law are side issues, at best; the real problem with Superman is its “bland and demoralizing vision” of an America without values. He describes the film’s Jonathan and Martha Kent at “ludicrously folksy stereotypes”; he condemns the fact that this Superman “doesn’t utter a word about ‘the American way,’” but instead “when he confronts Luthor at the film’s climax…insists his failings are what makes him human”; and that Superman’s core replaces patriotism with sentimentality: “Superman hasn’t assimilated to America, but to an unplaceable idea of niceness and self-affirmation.”

Well, as Jules Winnfield once said, allow me to retort.

I called this a politico-theological argument, because it is: it is an argument which is built out of assumptions about the moral importance, perhaps even the moral centrality, of being a part of a national community, a community that itself posits its own character—its own “way”—as reflecting, perhaps even instantiating, something unique and higher. Without being attached to a people and place, moral positions become bland: “niceness” is a characteristic which anyone can possess, and it betokens no sense of strength or specialness. Superman is, McCarthy is saying, just this guy with powers; he does not inspire, unlike Trump, who understands that the point of national leadership is to never be humiliated, to be “so strong” he doesn’t need to engage in violence (unless he chooses to, of course).

Thankfully there are at least some conservative Christians who still haven’t forgotten that the theology which actually emerged from the stories of the Bible, both the Old and New Testament, and in contrast to the idolatry which motivates so much of the MAGA cult, isn’t at all about strength but rather is all about acceptance: acceptance of individual choice and accountability, acceptance of one’s common and flawed mortality, acceptance of the equal dignity of all persons, good or bad, weak or strong, journeying through this earthly life. On that reading, Gunn’s Superman is a deeply religious film, telling the story of the struggles and the triumph—for the moment!—of a tremendously gifted man who cares deeply about his fellow beings (regarding Krypto: “He’s not even a very good dog—but he’s out there alone, and he’s probably scared”), despite his own many limitations (his final words in the movie, after Mr. Terrific leaves Superman in a huff: “I am such a jerk sometimes”). But I think we can go even deeper than that.

Long ago, back when the Blogosphere was a name that was actually recognized by many, I was part of a long discussion over what some scholars of religious belief and practice had terms “Moral Therapeutic Deism.” My engagement in that debate touched on Barak Obama, Rod Dreher, civil religion, and more, but I’d like to draw out just one element of it: the thought of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. And actually, I wouldn’t be surprised if McCarthy had been actually subtly signaling to all the Rousseau-haters out there when he described the “sentimentality” of Gunn’s Superman as consisting of “niceness and self-affirmation,” because that’s just a step or two away from one of Rousseau’s key claims: that modern morality is built, first, upon pity or compassion for others, and second, upon amour de soi, a concept usually translated as “self-love,” but which really connotes a positive sense of dignity, self-care, and accountability.

In any case, for Rousseau, modernity has robbed us of the possibility of a genuinely organic connection to a national community, or really any community identity at all; to take its place, there is the need to educate people in a religious sensibility that arguably is a direct ancestor of MTD. “The Creed of the Savoyard Priest” is a central text here; its ideas were foundational for much 19th-century liberal Christian theology, and frankly, that theology is as American as apple pie: God loves you. God has given you an inner sense of decency; don’t allow learned rationalizations to distract you from it. On the contrary, God wants you to follow your conscience, as that will allow you to best respect and serve and build community with others. As the Priest writes: “Feeling precedes knowledge. Since we do not learn to seek what is good for us and avoid what is bad for us, but get this desire from nature, in the same way the love of good and the hatred of evil are as natural to us as our amour de soi.”

I don’t deny for a moment that there is a potential for moral individualism here that can be, and in some ways absolutely has been, devastating to the moral conditions of modernity. And yet, modernity means more than just the worst aspects of individualism; it also means (as I wrote in that blog post 16 years ago) “the global regime of human rights, worldwide activism on behalf of the indebted and the poor, volunteerism and service in tens of thousands of places across the globe,” etc., etc., etc. How much are all the undeniably limited but nonetheless still real ways in which the world has improved, at least insofar as slavery, coverture, torture, and genocide, over the past two hundred years the result of “people absorbing anemic liberal doctrines about not shooting people who just want to get a better job or to express themselves, about recognizing the need to actually sit down and speak with and learn from those whom you had previously oppressed”? To connect this back to Superman, our hero’s defense of his involvement in the Boravian attack on Jarhanpur ultimately comes down to—and his contentious interview with Lois Lane makes this clear—one simple moral reality: “People were going to die!” Using super-powers to stop (again, for the moment!) a conflict because you don’t want people to die is, surely, pretty simplistic, pretty basic. It is also, well, compassionate; it is sentimental, it is nice.

And this, really, takes us back to the people, the community, that Gunn’s Superman does belong to: his parents in Smallville. As has been noted, past comic and cinematic incarnations of Jonathan and Martha Kent have tended to present them as “paragons of a certain kind of Americana nobility; strong, proud farmers from the heartland,” teaching their adopted son “all the right values and the responsibilities that come with his incredible abilities.” But Gunn makes them “normies” (by the way, this was something, as a Kansan, I recognized from the very first trailer; far from the stereotypical red barn with windmill and grain elevator, miles and miles from town, these are two far more typical rural residents of small-town Kansas in 2025, where the grain fields are overwhelmingly owned by large corporate actors: the Kents have a suburban ranch home and run cattle, and probably both have jobs in town on the side). Are they church-goers? One would guess. But churchgoing in small-town Kansas in the 21st-century isn’t and can’t be imagined as being what it was when Glenn Ford’s Jonathan Kent clapped young Clark on the shoulder just before dying of a heart attack in Donner’s 1978 Superman: The Movie. For better and for worse, that stoic, American Gothic image of the heartland has now all but disappeared. What’s in its place? A lot of good people (even if they are Trump votes, as Jonathan and Martha Kent almost certainly are), who go to church and embrace a message of Christian decency and sentiment—the sort of message that would lead Pa Kent to say, it what was clearly the moral center of the Superman, whatever anyone else might say later:

Parents aren’t for telling their children who they’re supposed to be. We are here to give y’all tools to help you make fools of yourselves all on your own. Your choices, Clark. Your actions. That’s what makes you who you are. Let me tell you something, son, I couldn’t be more proud of you.

Right there, we have parental love, we have tolerance, we have individual responsibility, we have dignity and respect. Perhaps theologically those virtues are “bland” enough, in McCarthy’s words, to not provide a foundation for strength; on the level of philosophy, I’m open to that argument. But insofar as actually lived lives are concerned—particularly the lived lives of Kansans that I know, including many whose politics I think are appalling, but whose support for families and friends and civic work are rock solid—I think this kind of morality, Superman’s morality, a morality that saves dogs and squirrels, a morality that refuses to cause harm to others, fails to prevent all possible harm, but then keeps on trying again and again anyway, is a damn good one. Sentimental yes, but inspiring too, I think. (And from all the memes that are apparently out there celebrating the wonderful, stupid, absolutely Superman-ish line "Kindness, maybe that's the new punk rock," maybe there are more people out there who agree with me, rather than McCarthy.)