Tuesday, December 30, 2008

Forty Mid-Life Lessons

1. For all except a rather small minority of people on this planet, probably nothing is more important than finding a partner you can make a loving, respectful, happy union with, and then keeping that union together through thick and thin. Compared to accomplishing that, just about every other failure shrinks into insignificance; compared to giving up on that task, just about every other success does the same.

2. Read. Start young, and don't ever stop.

3. Write. Poetry, fiction, criticism, songs, essays, letters, scholarship, personal diaries...it almost doesn't matter what.

4. Don't let all the things Karl Marx got wrong prevent you from learning from what he got right.

5. Be a patriot, not constitutionalist. (That is, love your homeland, not your homeland's government.)

6. Have or adopt or foster or spend time with children. There's nothing better.

7. Find a church, and stick with it; the more time you commit to it, the more truth you'll find both within and without it, and plus the your fellow parishioners won't bug you so much after a while.

8. Occasionally visit other churches too. You shouldn't spend your life wandering from one house of worship to the next, but it is good to learn what other people are looking for; it might help you see your own choice more clearly.

9. People who won't even acknowledge the upside of protectionist or socialist economics are people who have allowed Ayn Rand or P.J. O'Rourke to convince them that forms of life have no historical or material grounding, but rather are just things individuals make up as they go along. They're wrong.

10. Much as it compromises my own profession, this would be a better world if there were more social and economic opportunities not tied to getting an official piece of paper from a black-robed, accredited intellectual like me.

11. Vote.

12. Just about everybody likes some sort of fluff; practically everyone is some sort of geek. This is not to say that every idiosyncratic preoccupation is equally worthy--not everything is relative. But if you argue against others' obsessions, argue respectfully, because you have them yourself.

13. Take a pay cut rather than work in a cubicle; turn down the promotion in favor of the office with a window.

14. Manners and rituals and customs and uniforms and holidays are all important secondary goods: not absolute, but not to be casually dismissed either.

15. Take breakfast seriously: learn to how to make waffles, biscuits, potato cakes, fresh orange juice, maple syrup, poached eggs, cinnamon rolls. It's the most important meal of the day.

16. Commuting to work on a bicycle is good for the environment, good for your body, and good for your soul.

17. While others study romantics and agrarians for their poetry, study them instead for their ideas.

18. Occasional goofiness and irresponsibility can be a good thing.

19. Context almost always matters more than content.

20. Ideas can't give offense; you can only choose to take offense at those who deliver them.

21. A little Luddism never did anyone any harm.

22. Nearly all "expert" nutritional advice is flawed.

23. If at some point in your life you learn (or even just pick up a little bit of) a foreign language, don't make the mistake of forgetting it.

24. Derek and the Dominoes, John Denver, the Commodores, Jackson Brown, Blondie, ABBA, Electric Light Orchestra, Parliament-Funkadelic, Lou Reed, the Clash, Supertramp, Earth Wind and Fire, the Bee Gees, Carly Simon--all this, plus the Rolling Stones, Neil Diamond, Michael Jackson, Elton John, the Eagles, Talking Heads, Linda Ronstadt, David Bowie, Pink Floyd, and James Taylor at the height of their creative powers? Don't listen to the haters; the 1970s were the greatest decade in American pop-rock radio ever.

25. Plant a garden.

26. Aristotle (and Confucius, and Rousseau, and Tocqueville) was right: we are discursive, communal beings, who find ourselves most fully through fellowship and service and role-performance with other human beings. So don't take that individualism crap too seriously.

27. If you have an addiction, don't hide it, don't think you've got it under control, and don't allow yourself to believe it's just a problem with your self-image or self-esteem; get yourself into a legitimate, faith-centered 12-step program, and stick with it.

28. Slow down; take that family vacation in the car.

29. Play on the computer if you must, but Dungeons and Dragons will always be better with pencils, graph paper, and some 20-sided dice.

30. Subscribe to a daily newspaper. Read it.

31. Shop locally, especially for food. If you go to a farmers market, get to know the farmers, and find out where the food you buy comes from.

32. Move to a neighborhood that has sidewalks or quiet streets, where you can walk to church or the grocery store or the kids can walk to school. Then do so.

33. Naiveté gets a bad rap. Second naiveté especially so.

34. Take traditions seriously enough to be able to argue with and reject them; don't just leave them alone to die.

35. You can (and should) be liberal without being a liberal.

36. It probably doesn't matter too much if your partner isn't all that interested in your personal hobbies or what you do at work or what you do with your other friends. It does matter a lot if you can't explain to your partner why those things are important to you...or if you can't appreciate in turn what your partner explains to you.

37. Brown bag your lunch to work.

38. A truly humble person can't be humiliated.

39. In the end, after all the ethics and commandments and tough choices and hard judgments, as important as they are, never forget what this passage of scripture says truly matters.

40. Have fun.

Oh, and happy new year, everyone.

Friday, December 26, 2008

Friday Morning Videos: "Do They Know It's Christmas?"

Hope everyone had a good Christmas. And, if anyone knows, who is the guy at the back of the chorus who turns and laughs at the camera near the end of the video? I still can't place him.

Wednesday, December 24, 2008

Still.

Amongst those cultural critics who look upon modern life and see little that is admirable and even less which is sustainable, Bill McKibben definitely has a rather one-sided fan club. Whereas Wendell Berry, for example, can find readers and enthusiasts on both the right and left, McKibben's followers are almost always on the progressive side of things. This isn't surprising: he made his name with The End of Nature, a provocative book on global warming, then later followed-up on the environmental catastrophe theme with Maybe One, a book urging everyone to restrict themselves to reproducing only once. Folks whose complaints with modern life arise from religious or traditional concerns don't, for the most part, respond well these kind of deep ecological, vaguely or arguably anti-family pre-occupations.

I myself am not a huge McKibben fan, though I've read a lot of his work, and found much in it to learn from and admire. This year, I'm thinking a lot about the ideas he put forward in Hundred-Dollar Holiday, a wonderful and thoughtful--if not entirely liveable--essay on what a simpler, more local, less commercial Christmas might entail. Again, this isn't a message that is likely to resonate terribly well with you if, in the midst of whatever concerns you may have about the busyness and business of modern life, you're also trying to bring up four well-adjusted daughters in an ordinary, mid-sized American city, as we are. But then, we've compromised on localist resolutions before, and that hasn't stopped us from trying to take them as guides to our living anyway; Christmas wouldn't be any different. Besides, probably the most important point McKibben makes in that book is simply that Christmas festivities have always been adapted to one's time and place. A Christmas of noise and celebration, of gift-giving and light-stringing, of feasting and exuberance, is the legacy of the West's much poorer and much more agricultural past, when nothing provided more of a break from the routine of life than a little rowdiness and luxury and overeating. In the world of constant noise and selling and appointments and expectations we have today, trying to limit oneself, so as to turn the holiday into something different, makes good sense.

It's interesting that this same week I've been talking online with some folks about Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol. I've talked about my passion for that story a couple of times before, and it was fun to discuss it with others. One point which came out in our conversation was that the ideal which Dickens sketched out in that novella was not a Mckibben Christmas; Dickens very strongly believed (as was brought out in the Orwell essay on Dickens I mentioned in the latter post) in commerce and celebration and material things and festive times as forces for good. Of course, he believed in those things liberally, and crusaded against those individuals and institutions which worked against them from being within the reach of all men, especially the poor; but he did not imagine Christmas as a reason or occasion for us to attempt to rise above such concerns entirely. Clearly, McKibben and Dickens live in two very different worlds (though I wouldn't be surprised if, in the end, their perspectives on and faith in Christianity and the Bible weren't pretty much the same). The rest of us, hounded by the overwrought expense and rushed pace of the holiday around us on the one hand, yet also desiring to partake of that good cheer which Dickens (as well as others, including our own experiences) has taught us to understand as being a legitimate part of the "Good News" of the season on the other, are stuck in between.

So maybe we just muddle along, in our usual ameliorative way, looking for some compromised simplicity and some arbitrary spaces to step back and step away from it all and be still in the midst of our modern busyness. I think it can be done. In the aforementioned post on Dickens's masterpiece, I mentioned another masterful storyteller, Garrison Keillor, whom I'm just liberal enough and Christian enough and sentimental enough to be just about the perfect audience member for. His annual Christmas broadcasts are important events in my yearly routine, and one monologue of his, given back in 2001, included a passage that seems appropriate here:

This is the best parts of Christmas, the part just before it starts. There are these whole big patches of serenity that open up, and you feel this peace of Christmas, when the rush has sort of quieted down a little bit and there's not that much that remains to be done--or it's too late to do what needs to be done--and you sit and enjoy the quiet. You walk outside on a Christmas eve after you've done with the supper, and you're going to go off to church, and you look up at this great vast starry sky, and at black branches poking up into it, and you just stand there and you breathe it all in. That's Christmas: that part, right there, that's the peace of Christmas. Or on Christmas Day, when the company has not come yet and everything's done--the cookies are all baked, and you've done your turn around the living room with the vacuum, and the table is all set--you have this little twenty minutes, this little half-hour, and you just drink it all in: it's such a lovely, lovely time, when you can just sit and think back about all the Christmases that you remember.

Twenty minutes doesn't seem like much; certainly it's not any kind of hundred-dollar manifesto, looking to change one's routine entirely. But it is something; it is a bit of stillness that keeps you from losing sight of that alternative entirely. And maybe one of the reasons our North European/New England shaping of the holiday has stayed with us for so long is that our memory of the cold and dark--or the actual experience of it--gives those moments of stillness and memory an edge, an advantage against all those other things, as worthy and appropriate as they may be, which too often drag us away from homes and hearths where siting down and counting blessing and breathing it all in is a little bit easier.

This Christmas, I'm thinking of the way, as a boy, I would try to find a way to get myself alone in the living room late on Christmas Eve--a difficult thing, in a large and noisy home with eight siblings, but I usually managed it just the same--where I would light the candles on our Swedish Angel Chimes, and listen to the bells ring. And I'm thinking of Melissa's and my first Christmas as a married couple; we returned home late on Christmas Eve from a visit to my grandparent's, had a light supper, then walked to local Catholic parish, and attended a midnight mass. Walking home on that cold and clear Utah night, returning to our scrawny tree in our underheated (and soon to be condemned) apartment, where we lit some candles and put on some music and sat down. It was like everything was on pause; everything was before us, waiting for us to begin.

And, of course, it did begin, and it's still going. Four daughters will be waking up tomorrow morning, looking for evidence that Santa Claus had come (which he will have, of course), and their bound to be noisy. And then the day will be upon us, and we'll have stuff to do. But we'll have had the night before--and next year, God willing, we'll have another cold and still night before, and many more after that as well.

I'll finish with my father-in-law's favorite carol, and one of mine as well:

Still, still, still,

One can hear the falling snow.

For all is hushed,

The world is sleeping,

Holy Star its vigil keeping.

Still, still, still,

One can hear the falling snow.

Sleep, sleep, sleep,

'Tis the eve of our Savior's birth.

The night is peaceful all around you,

Close your eyes,

Let sleep surround you.

Sleep, sleep, sleep,

'Tis the eve of our Savior's birth.

Dream, dream, dream,

Of the joyous day to come.

While guardian angels without number,

Watch you as you sweetly slumber.

Dream, dream, dream,

Of the joyous day to come.

Here's wishing you a joyous day tomorrow, everyone--and maybe a quiet twenty minutes or so, lying still in bed, before it all begins. Merry Christmas.

Friday, December 19, 2008

Friday Morning Videos: "Gabriel's Message"

I shouldn't mock; I loved this album, and this track, when I first encountered it at college. Still do.

Wednesday, December 17, 2008

Welcome, Damon

Oh, and what about his point? Really, between Damon's thoughts, and Steve Waldman's much lengthier take here, there's nothing more to say. Obviously Obama is not a socially conservative Christian, but his choice of Warren--assuming we are to read anything into this ceremonial choice at all, which unlike Damon I think maybe we can, assuming we don't allow ourselves to get carried away--shows him to be a little more serious, maybe even a little more orthodox, than either those on the secular left or the theocon right are willing to admit. Insofar as conservative Christian voters are concerned, yes, sure, it would be easy to deride Warren and by extension his connection to our new president; with his rhetoric of the "purpose-driven life," he can be dismissed as an exponent of Christianity Lite, of "moralistic therapeutic deism" as the current phrase has it. But then, what would one make of the inaugural of President Eisenhower, which Damon helpfully links to, with its pious, serious, but also thoroughly nondenominational prayer language at its beginning? In a liberal society, the best context for expressions of piety are ones which emphasize the service, generosity, charity and unity which dedicating one's life to God ought to make possible. Warren exemplifies this. And as for those on the opposite side, who feel that Warren's Biblically grounded, socially conservative views somehow compromises what he can represent in the context of an inaugural prayer, that it's a rebuke to Obama's winning coalition...well, that buys into the exactly the same for-us-or-against-us mentality which cultural warriors on the right depend upon. You'd think Obama's desire to bring rivals together would have shown his supporters on the left that such isn't the kind of game he plays.

[Update, 12/18--Damon's just put up a follow-up post, and he agrees with me. So there.]

Tuesday, December 16, 2008

On Surrogacy, Class, and Conservatism

I wouldn't disagree with either of those accusations, but that's an old point for me. The advancement of socially conservative goals is and ought to be linked, as far as I'm concerned, with a serious concern for social justice, meaning fair distribution and opportunity, and economic and civic equality. By the same token, the attainment of social justice cannot elide the importance of respecting, conserving, and sometimes even promoting traditional attachments, of both a communitarian and a moral nature. But this Christian democratic point of mine is one I've made often before, and I no more expect to find a lot of company in sharing it than I did when I first started sketching it out over five years ago. So Matt's head-scratching response to some of the confused snarks at Kuczynski's piece didn't surprise me.

I was, however, pleasantly surprised at the appearance of a new favorite blogger of mine, "Hector," in Matt's comboxes. Hector's a graduate student whose focus is agriculture and botany rather than the social consequences of the behavior of oblivious rich New York liberals (and feel free to read the whole piece--you may find some sympathy for Kuczyski's blight, but her inability to do more than gesture in the direction of the moral and class dilemmas involved in employing a surrogate mother for one's own child, before rushing back to her money-soaked lifestyle portrait is grating in the extreme) but his grounding in, and international perspective on, the whole range of natural law and Christian socialist thought makes him a good interlocutor in regards to the intersection of morality and liberal individualism, as I discovered in some of the discussions about Proposition 8 on Hugo Swchwyzer's blog. Certainly he handles himself in the comboxes than some others who have stumbled into this latest iteration of the argument over surrogate motherhood. I'm thinking here of Erin Manning, a smart and capable commenter who recently took over at Rod Dreher's blog for a stint. She highlights the questions posed by a couple of pieces which appeared in the Wall Street Journal; the first, Thomas Frank's take on Kuczynski's self-indulgent piece (the fact that it's a leftist like Frank attacking what Manning calls the "new secular morality" ought to have drawn her attention), and the second, a hand-wringing bit of reportage about how the upper-middle classes may have to let the domestic help go in these bad economic times, especially if the choice is between employing a nanny and getting Botox treatments. Erin recognizes, to her credit, that there is a real linkage between these two pieces, but she seems unable to fully articulate it. The common theme she names capably: "this has to do with our culture's acceptance of the notion that we can outsource our children's upbringing [or their birth] to temporary workers without this damaging our children [or family relationships] in any way." What is needed there is some good old Marxist rhetoric, such as Hector's Christian socialism provides: rhetoric like alienation, or better, commodification. In other words, this is a matter of how modern economic life and modern technology can potentially commodify that which ought to, somehow or another, maintain an essential connection to the natural, the personal, the intimate. To lose that connection is to--not always, but often--lose our ability to draw upon the traditions, roles, and associations which are sustained by those natural grounds, and hence to be that much more at a loss when we try to figure out how to be parents, employers, caregivers and neighbors, and so much more. Take it away, Alasdair McIntyre.

Manning's almost-but-not-quite formulation of the linkage here is emphasized by her refusal to see this as a "mommy wars" issue. Now I don't know exactly what she has in mind while speaking of the mommy wars, and no doubt a great deal of harmful and false judgments are thrown about in the midst of that debate. But nonetheless it is a real debate, and asking questions about how the rich vs. the poor, or the SAHMs vs. the professionally working mothers, or the traditional parents vs. the egalitarian parents, choose to--or are able to--prioritize or re-organize such impossibly basic things like having a baby, feeding a child, cleaning a house, or playing with one's children, is an intensely important debate, one involving difficult choices and heavy judgments. (Laura McKenna has been my preferred guide to these arguments for years now; check out this blog conference she held a few years back as good a place to start.) Perhaps those judgments seem too often to result in unfairly pitting women against one another, but I see that as primarily a function of people and perspectives which begin the arguments by remove economic and structural issues from consideration, meaning that the majority of those who get to set maternal and paternal leave policies, those who develop and drive and advertise on behalf of lifestyle choices and technological enablers of such, get a free pass. And that's not the way it should be.

Other smart conservative commenters who get into this debate, like James Poulos, seem to make the same mistakes. In James's case, he figures that surrogate motherhood will never be particularly common (though one of his fellow bloggers disagrees) if only because there will be "something" that will leave the majority of those involved in said transactions feeling vaguely guilty and uncomfortable. And if that turns out not to be the case, then he reserves the right to criticize those who choose surrogacy simply as a way of avoiding the messy, painful, dangerous, natural work of pregnancy, as "a greater inconvenience than they feel their child is worth....unless, of course, she was earning millions for doing something that for some reason required she not grow and birth me, and then she gave me enough of those millions, etc., etc." There are a lot of difficult questions here, questions about the opportunities which globalization and technology have thrown into the laps of many (though mostly into the laps of the super-rich like Kuczynski); eschewing or being cavalier about the economics which put these socially conservative considerations before our eyes in the first place is not the best way to answer them.

Friday, December 12, 2008

Friday Morning Videos: "Breakout"

(And yeah, I missed a week. Sorry.)

Thursday, December 11, 2008

The Worst Christmas Specials Ever

In the meantime, it's time for some holiday posts, and there's no better one to start with than this oldie-but-goodie from John Scalzi, who wrote it ages ago (like around 2004, or even earlier): "The Ten Least Successful Holiday Specials of All Time." It's long since made the rounds in the blogosphere, probably multiple times, but I still find it just about the funniest thing I've ever read online. Enjoy.

An Algonquin Round Table Christmas (1927)

Alexander Woolcott, Franklin Pierce Adams, George Kaufman, Robert Benchley and Dorothy Parker were the stars of this 1927 NBC Red radio network special, one of the earliest Christmas specials ever performed. Unfortunately the principals, lured to the table for an unusual evening gathering by the promise of free drinks and pirogies, appeared unaware they were live and on the air, avoiding witty seasonal banter to concentrate on trashing absent Round Tabler Edna Ferber’s latest novel, Mother Knows Best, and complaining, in progressively drunken fashion, about their lack of sex lives. Seasonal material of a sort finally appears in the 23rd minute when Dorothy Parker, already on her fifth drink, can be heard to remark, “one more of these and I’ll be sliding down Santa’s chimney.” The feed was cut shortly thereafter. NBC Red’s 1928 holiday special “Christmas with the Fitzgeralds” was similarly unsuccessful.

Alexander Woolcott, Franklin Pierce Adams, George Kaufman, Robert Benchley and Dorothy Parker were the stars of this 1927 NBC Red radio network special, one of the earliest Christmas specials ever performed. Unfortunately the principals, lured to the table for an unusual evening gathering by the promise of free drinks and pirogies, appeared unaware they were live and on the air, avoiding witty seasonal banter to concentrate on trashing absent Round Tabler Edna Ferber’s latest novel, Mother Knows Best, and complaining, in progressively drunken fashion, about their lack of sex lives. Seasonal material of a sort finally appears in the 23rd minute when Dorothy Parker, already on her fifth drink, can be heard to remark, “one more of these and I’ll be sliding down Santa’s chimney.” The feed was cut shortly thereafter. NBC Red’s 1928 holiday special “Christmas with the Fitzgeralds” was similarly unsuccessful.

The Mercury Theater of the Air Presents the Assassination of Saint Nicholas (1939)

Listeners of radio’s Columbia Broadcasting System who tuned in to hear a Christmas Eve rendition of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol were shocked when they heard what appeared to be a newscast from the north pole, reporting that Santa’s Workshop had been overrun in a blitzkrieg by Finnish proxies of the Nazi German government. The newscast, a hoax created by 20-something wunderkind Orson Wells as a seasonal allegory about the spread of Fascism in Europe, was so successful that few listeners stayed to listen until the end, when St. Nick emerged from the smoking ruins of his workshop to deliver a rousing call to action against the authoritarian tide and to urge peace on Earth, good will toward men and expound on the joys of a hot cup of Mercury Theater of Air’s sponsor Campbell’s soup. Instead, tens of thousands of New York City children mobbed the Macy’s Department Store on 34th, long presumed to be Santa’s New York embassy, and sang Christmas carols in wee, sobbing tones. Only a midnight appearance of New York mayor Fiorello LaGuardia in full Santa getup quelled the agitated tykes. Welles, now a hunted man on the Eastern seaboard, decamped for Hollywood shortly thereafter.

Listeners of radio’s Columbia Broadcasting System who tuned in to hear a Christmas Eve rendition of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol were shocked when they heard what appeared to be a newscast from the north pole, reporting that Santa’s Workshop had been overrun in a blitzkrieg by Finnish proxies of the Nazi German government. The newscast, a hoax created by 20-something wunderkind Orson Wells as a seasonal allegory about the spread of Fascism in Europe, was so successful that few listeners stayed to listen until the end, when St. Nick emerged from the smoking ruins of his workshop to deliver a rousing call to action against the authoritarian tide and to urge peace on Earth, good will toward men and expound on the joys of a hot cup of Mercury Theater of Air’s sponsor Campbell’s soup. Instead, tens of thousands of New York City children mobbed the Macy’s Department Store on 34th, long presumed to be Santa’s New York embassy, and sang Christmas carols in wee, sobbing tones. Only a midnight appearance of New York mayor Fiorello LaGuardia in full Santa getup quelled the agitated tykes. Welles, now a hunted man on the Eastern seaboard, decamped for Hollywood shortly thereafter.

Ayn Rand’s A Selfish Christmas (1951)

In this hour-long radio drama, Santa struggles with the increasing demands of providing gifts for millions of spoiled, ungrateful brats across the world, until a single elf, in the engineering department of his workshop, convinces Santa to go on strike. The special ends with the entropic collapse of the civilization of takers and the spectacle of children trudging across the bitterly cold, dark tundra to offer Santa cash for his services, acknowledging at last that his genius makes the gifts — and therefore Christmas — possible. Prior to broadcast, Mutual Broadcast System executives raised objections to the radio play, noting that 56 minutes of the hour-long broadcast went to a philosophical manifesto by the elf and of the four remaining minutes, three went to a love scene between Santa and the cold, practical Mrs. Claus that was rendered into radio through the use of grunts and the shattering of several dozen whiskey tumblers. In later letters, Rand sneeringly described these executives as “anti-life.”

In this hour-long radio drama, Santa struggles with the increasing demands of providing gifts for millions of spoiled, ungrateful brats across the world, until a single elf, in the engineering department of his workshop, convinces Santa to go on strike. The special ends with the entropic collapse of the civilization of takers and the spectacle of children trudging across the bitterly cold, dark tundra to offer Santa cash for his services, acknowledging at last that his genius makes the gifts — and therefore Christmas — possible. Prior to broadcast, Mutual Broadcast System executives raised objections to the radio play, noting that 56 minutes of the hour-long broadcast went to a philosophical manifesto by the elf and of the four remaining minutes, three went to a love scene between Santa and the cold, practical Mrs. Claus that was rendered into radio through the use of grunts and the shattering of several dozen whiskey tumblers. In later letters, Rand sneeringly described these executives as “anti-life.”

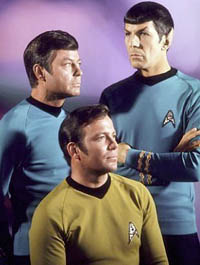

The Lost Star Trek Christmas Episode: “A Most Illogical Holiday” (1968)

Mr. Spock, with his pointy ears, is hailed as a messiah on a wintry world where elves toil for a mysterious master, revealed to be Santa just prior to the first commercial break. Santa, enraged, kills Ensign Jones and attacks the Enterprise in his sleigh. As Scotty works to keep the power flowing to the shields, Kirk and Bones infiltrate Santa’s headquarters. With the help of the comely and lonely Mrs. Claus, Kirk is led to the heart of the workshop, where he learns the truth: Santa is himself a pawn to a master computer, whose initial program is based on an ancient book of children’s Christmas tales. Kirk engages the master computer in a battle of wits, demanding the computer explain how it is physically possible for Santa to deliver gifts to all the children in the universe in a single night. The master computer, confronted with this computational anomaly, self-destructs; Santa, freed from mental enslavement, releases the elves and begins a new, democratic society. Back on the ship, Bones and Spock bicker about the meaning of Christmas, an argument which ends when Scotty appears on the bridge with egg nog made with Romulan Ale.

Mr. Spock, with his pointy ears, is hailed as a messiah on a wintry world where elves toil for a mysterious master, revealed to be Santa just prior to the first commercial break. Santa, enraged, kills Ensign Jones and attacks the Enterprise in his sleigh. As Scotty works to keep the power flowing to the shields, Kirk and Bones infiltrate Santa’s headquarters. With the help of the comely and lonely Mrs. Claus, Kirk is led to the heart of the workshop, where he learns the truth: Santa is himself a pawn to a master computer, whose initial program is based on an ancient book of children’s Christmas tales. Kirk engages the master computer in a battle of wits, demanding the computer explain how it is physically possible for Santa to deliver gifts to all the children in the universe in a single night. The master computer, confronted with this computational anomaly, self-destructs; Santa, freed from mental enslavement, releases the elves and begins a new, democratic society. Back on the ship, Bones and Spock bicker about the meaning of Christmas, an argument which ends when Scotty appears on the bridge with egg nog made with Romulan Ale.

Filmed during the series’ run, this episode was never shown on network television and was offered in syndication only once, in 1975. Star Trek fans hint the episode was later personally destroyed by Gene Roddenberry. Rumor suggests Harlan Ellison may have written the original script; asked about the episode at 1978’s IgunaCon II science fiction convention, however, Ellison described the episode as “a quiescently glistening cherem of pus.”

Bob & Carol & Ted & Santa (1973)

This ABC Christmas special featured Santa as a happy-go-lucky swinger who comically wades into the marital bed of two neurotic 70s couples, and also the music of the Carpenters. It was screened for television critics but shelved by the network when the critics, assembled at ABC’s New York offices, rose as one to strangle the producers at the post-viewing interview. Joel Siegel would later write, “When Santa did his striptease for Carol while Karen Carpenter sang ‘Top of the World’ and peered through an open window, we all looked at each other and knew that we television critics, of all people, had been called upon to defend Western Civilization. We dared not fail.”

This ABC Christmas special featured Santa as a happy-go-lucky swinger who comically wades into the marital bed of two neurotic 70s couples, and also the music of the Carpenters. It was screened for television critics but shelved by the network when the critics, assembled at ABC’s New York offices, rose as one to strangle the producers at the post-viewing interview. Joel Siegel would later write, “When Santa did his striptease for Carol while Karen Carpenter sang ‘Top of the World’ and peered through an open window, we all looked at each other and knew that we television critics, of all people, had been called upon to defend Western Civilization. We dared not fail.”

A Muppet Christmas with Zbigniew Brzezinski (1978)

A year before their rather more successful Christmas pairing with John Denver, the Muppets joined Carter Administration National Security Advisor Brezezinski for an evening of fun, song, and anticommunist rhetoric. While those who remember the show recall the pairing of Brzezinki and Miss Piggy for a duet of “Winter Wonderland” as winsomely enchanting, the scenes where the NSA head explains the true meaning of Christmas to an assemblage of Muppets dressed as Afghan mujahideen was incongruous and disturbing even then. Washington rumor, unsupported by any Carter administration member, suggests that President Carter had this Christmas special on a repeating loop while he drafted his infamous “Malaise” speech.

A year before their rather more successful Christmas pairing with John Denver, the Muppets joined Carter Administration National Security Advisor Brezezinski for an evening of fun, song, and anticommunist rhetoric. While those who remember the show recall the pairing of Brzezinki and Miss Piggy for a duet of “Winter Wonderland” as winsomely enchanting, the scenes where the NSA head explains the true meaning of Christmas to an assemblage of Muppets dressed as Afghan mujahideen was incongruous and disturbing even then. Washington rumor, unsupported by any Carter administration member, suggests that President Carter had this Christmas special on a repeating loop while he drafted his infamous “Malaise” speech.

The Village People in Can’t Stop the Christmas Music — On Ice! (1980)

Undeterred by the miserable flop of the movie Can’t Stop the Music!, last place television network NBC aired this special, in which music group the Village People mobilize to save Christmas after Santa Claus (Paul Lynde) experiences a hernia. Thus follows several musical sequences — on ice! — where the Village People move Santa’s Workshop to Christopher Street, enlist their friends to become elves with an adapted version of their hit “In The Navy,” and draft film co-star Bruce Jenner to become the new Santa in a sequence which involves stripping the 1976 gold medal decathlon winner to his shorts, shaving and oiling his chest, and outfitting him in fur-trimmed red briefs and crimson leathers to a disco version of “Come O Ye Faithful.” Peggy Fleming, Shields and Yarnell and Lorna Luft co-star.

Undeterred by the miserable flop of the movie Can’t Stop the Music!, last place television network NBC aired this special, in which music group the Village People mobilize to save Christmas after Santa Claus (Paul Lynde) experiences a hernia. Thus follows several musical sequences — on ice! — where the Village People move Santa’s Workshop to Christopher Street, enlist their friends to become elves with an adapted version of their hit “In The Navy,” and draft film co-star Bruce Jenner to become the new Santa in a sequence which involves stripping the 1976 gold medal decathlon winner to his shorts, shaving and oiling his chest, and outfitting him in fur-trimmed red briefs and crimson leathers to a disco version of “Come O Ye Faithful.” Peggy Fleming, Shields and Yarnell and Lorna Luft co-star.

Interestingly, there is no reliable data regarding the ratings for this show, as the Nielsen diaries for this week were accidentally consumed by fire. Show producers estimate that one in ten Americans tuned in to at least part of the show, but more conservative estimates place the audience at no more than two or three percent, tops.

A Canadian Christmas with David Cronenberg (1986)

Faced with Canadian content requirements but no new programming, the Canadian Broadcasting Company turned to Canadian director David Cronenberg, hot off his success with Scanners and The Fly, to fill the seasonal gap. In this 90-minute event, Santa (Michael Ironside) makes an emergency landing in the Northwest Territories, where he is exposed to a previously unknown virus after being attacked by a violent moose. The virus causes Santa to develop both a large, tooth-bearing orifice in his belly and a lustful hunger for human flesh, which he sates by graphically devouring Canadian celebrities Bryan Adams, Dan Ackroyd and Gordie Howe on national television. Music by Neil Young.

Faced with Canadian content requirements but no new programming, the Canadian Broadcasting Company turned to Canadian director David Cronenberg, hot off his success with Scanners and The Fly, to fill the seasonal gap. In this 90-minute event, Santa (Michael Ironside) makes an emergency landing in the Northwest Territories, where he is exposed to a previously unknown virus after being attacked by a violent moose. The virus causes Santa to develop both a large, tooth-bearing orifice in his belly and a lustful hunger for human flesh, which he sates by graphically devouring Canadian celebrities Bryan Adams, Dan Ackroyd and Gordie Howe on national television. Music by Neil Young.

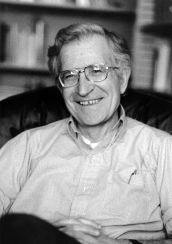

Noam Chomsky: Deconstructing Christmas (1998)

This PBS/WGBH special featured linguist and social commentator Chomsky sitting at a desk, explaining how the development of the commercial Christmas season directly relates to the loss of individual freedoms in the United States and the subjugation of indigenous people in southeast Asia. Despite a rave review by Z magazine, musical guest Zach de la Rocha and the concession by Chomsky to wear a seasonal hat for a younger demographic appeal, this is known to be the least requested Christmas special ever made.

This PBS/WGBH special featured linguist and social commentator Chomsky sitting at a desk, explaining how the development of the commercial Christmas season directly relates to the loss of individual freedoms in the United States and the subjugation of indigenous people in southeast Asia. Despite a rave review by Z magazine, musical guest Zach de la Rocha and the concession by Chomsky to wear a seasonal hat for a younger demographic appeal, this is known to be the least requested Christmas special ever made.

Christmas with the Nuge (2002)

Spurred by the success of The Osbournes on sister network MTV, cable network VH1 contracted zany hard rocker Ted Nugent to help create a “reality” Christmas special.  Nugent responded with a special that features the Motor City Madman bowhunting, and then making jerky from, four calling birds, three French hens, two turtle doves, and a partridge in a pear tree, all specially flown in to Nugent’s Michigan compound for the occasion. In the second half of the hour-long special, Nugent heckles vegetarian Night Ranger/Damn Yankees bassist Jack Blades into consuming three strips of dove jerky. Fearing the inevitable PETA protest, and boycotts from Moby and Pam Anderson, VH1 never aired the special, which is available solely by special order at the Nuge Store on TedNugent.com.

Nugent responded with a special that features the Motor City Madman bowhunting, and then making jerky from, four calling birds, three French hens, two turtle doves, and a partridge in a pear tree, all specially flown in to Nugent’s Michigan compound for the occasion. In the second half of the hour-long special, Nugent heckles vegetarian Night Ranger/Damn Yankees bassist Jack Blades into consuming three strips of dove jerky. Fearing the inevitable PETA protest, and boycotts from Moby and Pam Anderson, VH1 never aired the special, which is available solely by special order at the Nuge Store on TedNugent.com.

I still crack up when I get to the Ayn Rand special, with its whiskey tumblers and "anti-life" invective. And, of course, any sentence that actually includes the words "Shields and Yarnel" is, by definition, hilarious.

Friday, December 05, 2008

The Problem with Our Elites

I had to, however, take the time to note this wonderful and thoughtful post by Ross Douthat. Ross is almost always smart, but this post, on the pitfalls, mistakes, and vices of our current American economic elites, as compared with the elites of different eras and in different places, is simply brilliant. It’s filled with interesting ideas (such as the possibility that the elite which Tom Wolfe described 20 years ago has perhaps managed to both combine the worst and lose the best characteristics of American elites both past and present), and moreover, it’s not unwilling to indict its author as being a member of—and thus perhaps possessing some of the same flaws—that very cohort. All this, plus a Spider-Man reference. It’s great. There's something for everyone--liberal or communitarian or conservative or socialist or egalitarian or aristocrat--to chew on therein. Go and read it.

Friday, November 28, 2008

Friday Morning Videos: "Cars"

Good luck digesting, everyone.

Thursday, November 27, 2008

This Thanksgiving...

I'm thankful for friends who support us and humor us and counsel us when we're stressed and worried and in trouble.

I'm thankful for peers and acquaintances, both far and near, both old and new, all of whom remind me--whether they realize it or not--never to let the bad times crowd out all the good.

I'm thankful for parents who raised me well.

I'm thankful for a church filled with fellow members who are there to serve (and, with occasional sharpness, to reprove) each other as we struggle through life, making foolish choices along with wise ones, and then, when all is said and done, to help each another put things back together again.

Most of all, I'm thankful for God's grace this Thanksgiving, because I'd be nothing without it. And really, today, that's all that needs to be said.

Happy Thanksgiving, everyone! And now, onward into the rest of the holiday season. Let's see if we can get out of this one only slightly further in debt than we were before for a change.

Friday, November 21, 2008

Friday Morning Videos: "Piano in the Dark"

Wednesday, November 19, 2008

The Italians Love Me!

So I've been getting a bunch of hits from L'Espresso, arguably the leading newsmagazine in Italy. Following the links back, I discover that this blog has been deemed (forgive the no doubt lousy translation; I'm depending on Babel Fish here) an "authoritative site for entertainment and infomation." I outrank the RealClearPolitics, Slashdot, Joseph Stiglitz and Brad DeLong.

Well, I'm honored. Confused and a little disbelieving, but definitely honored.

Anyone who has any connections to Italy--or, for that matter, can read Italian, and thus can perhaps provide a fuller explanation here--want to pass along my thanks to the appropriate parties? Thanks, I appreciate it.

P.S. It occurs to me that maybe someone just thought it was cool that my blog uses a Latin phrase as its name.

Monday, November 17, 2008

To Boldly Go Where No Pop Culture Storytelling Phenomenon Has Gone Before

Ross Douthat has alreacy voiced some basic concerns here, and they are concerns that every geek ought to take seriously--just what kind of "reboot" is this? Is it a mere prequel? Is it a re-imagination of the whole premise of the series? Something in between? Something more? The leaks thusfar have been in some ways promising, but in other ways sobering, suggesting that what J.J. Abrams is bringing to the franchise is a lot of up-to-date Star Wars-style punching, with a bildungsroman pasted on top, and not much more. Well, as someone who has stood in line for opening night for more than a few Star Trek films, all I can say for sure is that we'll see.

I have a deeper concern though, which I think the trailer begs to be answered, and which I don't even know if I can frame as a question properly. But let me try anyway.

Just about every other pop culture property that Hollywood film studios or cable television networks have appropriated for the sake of creating new entertainments over the past century did not start out tied to a visualization associated with particular actors. James Bond was a series of books, Batman was a comic book, and so forth. Through all the films since, obviously certain cinematic conventions and expectations formed, but still, the fact remains that those conventions and expectations were not foundational. Daniel Craig may be measured against Sean Connery in the eyes of critics and movie-goers, but nobody really believes that Sean Connery was, in some literal sense, the "original" Bond. The same goes for Christian Bale (or Michael Keaton, or Adam West)--there's a Batman that can be gone back to, by screenwriters, by producers, by viewers, which is not Christian Bale or any of the rest.

Can that really be possible with Star Trek? Of course there was Gene Roddenberry there at the beginning, and dozens of other writers and technicians creating that series. But, as anyone who has been alive at any point since 1966 knows, William Shatner is James Tiberius Kirk. And Leonard Nimoy is Spock, and Deforest Kelley is Dr. McCoy, and so forth. They inhabited those roles, defined those roles, through not just the original series but also the cartoon series and the movies and all the novelizations and all the fiction (and all the fan fiction) which followed: millions and millions of words and images, all of which take that hair, that accent, that glance, that diction, all the composite elements of an actor's recorded performance, as a given in one's imagination of, and identification with, a character. Can you really get away from that?

Perhaps one could point to some successful movies that have been made of television shows where the main character was deeply identified with the person to who played him or her: Mel Gibson playing Maverick, for instance, or Nicole Kidman playing Samantha from Bewitched. But neither of those stories were treated--either in their original incarnations, or in their remakes, or by their fans in either case--with anywhere near the seriousness with which Star Trek has been (I would argue deservedly) been taken. Well, how about Battlestar Galactica, then? As Ross observed, making somewhat the same point I am making here, BG "was never a pop culture phenomenon along the lines of Trek" (and I would add it was never as character-centric as the original Trek was, besides the obvious point that it didn't last nearly as long). So the question, for me at least, remains unresolved.

We still don't know, I suppose, whether or not a successful re-imagining, in a visual medium, of a story-telling tradition that has so powerfully and for so long existed in our imagination in its own pre-existing visual medium, is at all possible. All this won't stop me from pre-ordering tickets, of course. I mean, watching the movie is the only way to find out.

Friday, November 14, 2008

Friday Morning Videos: "It's a Mistake"

I was, of course, a politics geek in junior high and high school, and remember--little Reagan fan that I was--making a lengthy and pretentious historical analysis and critique of this song at one point. Cold War, first strike capability, mutually assured destruction, detente, Soviet paranoia, all of it. Man, I loved Men at Work. Them and War Games.

Thursday, November 13, 2008

Personal Thoughts on Proposition 8

2. What do I think of my church's involvement in pushing the proposition? I have mixed feelings. Part of me has long wished my church would get more political, partly because I think religious voices need to be contended over back and forth in the public realm, partly because I think my church has ideas which could be a helpful contribution to that continuing contention which is modern democratic public life, and partly because--and this is important--by getting political, I hope that my church (which is, by any reasonable measure, still very much a fairly inwardly focused, fairly authoritarian institution) will learn some structural from those modern democratic exigencies, and be therefore better able to handle disagreements and compromises. So yes, the political scientist and fan of organized democratic action in me admires this move by my church, admires its ability to harness foot soldiers and efficient lines of communication in the service of political goal, and I feel this way even while thinking that--pragmatically speaking--more harm than good, in the long run, will come to my church because of its involvement in this particular effort, to say nothing of all the misunderstandings and anger and potential harms that may come to the citizens of California, both gay and straight, because of it.

3. Would I have voted for Proposition 8 if I'd lived in California? I think probably yes, reluctantly.

3a. "I think probably," because I don't live in California, and therefore I'm not confronted directly by personal situations and frustrations and aspirations which could have pulled my beliefs one way or another. As I've said before, arguments over tradition and marriage, in contrast to arguments over, say, abortion, are the sort of thing that "I simply nod my head in regards to, acknowledging their importance...in the abstract, but finding the practical efforts involved in the issue often misconceived and directed against the wrong target." Consequently, I could easily see me being swayed away from my tentative, somewhat theoretical support for it if the issue had confronted me more starkly.

3b. "Yes" for, I think, four reasons:

1) because my church asked me to (more on that below);

2) because I agree with some (but not all) of the philosophical arguments which my church and others who pushed for the proposition adduced as part of their case for the proposition (again, more on that below);

3) because, all things considered, I will almost always side with any proposition or referendum that involves setting matters directly before voters and thereby demands of them democratic deliberation and legislative compromise, rather than contenting ourselves with all-or-nothing decisions issued by courts (this is my wonky, political science preference for democracy coming out again);

3) because--and this is important--it was a narrowly focused proposition, one which would have re-established a formal distinction between same-sex relationships and heterosexual marriages in the state of California, but which would not have removed any substantive rights that gay couples currently enjoy under state law.

3c. "Reluctantly" for at least two reasons:

1) because California is almost certainly the wrong place for this kind of struggle: it is far too large and too diverse to be, I think, responsibly conceived of as an arena wherein an argument about what a community wants or expects or believes when it comes to marriage could be worked out (and if no such arena is being conceived, then we're apparently not talking about collective self-government, but rather than just tyrannies of courts or majorities, take your pick, and I don't want any part in that);

2) because the specific political arguments which the "Yes on 8" side made use of--as opposed to the more tentative and general philosophical ones which I, in part, agree with--were often complete paranoia and nonsense, and such crummy and inflammatory arguments are enough to make me want to vote against something in principle, even if I see the general point of the proposition.

4. In reference to 3b.2 (good grief, I'm writing a lawyer's brief here)...what do I see as the general point of the proposition? A great many people--not entirely accurately, I think, but entirely legitimately just the same--see its general point as one of hate and contempt, of moral busybodies cobbling together a majority and shoving their preferences down the throats of a tolerant and open-minded people. I'm sure there was some of that at play, amongst the thinking of my own people as well as the many others who turned out to pass Proposition 8. But to me, the general point of the proposition was one of drawing distinctions. I do happen to accept the deep cultural and/or communitarian and/or conservative presumption at work behind most traditionalist thinking about marriage: that is, I believe that civilized society depends upon the sustaining of certain norms (like heterosexual marriage), I believe that many (not all, but many) norms reflect essential characteristics of the way the majority of human beings have historically related and will continue to relate to one another, and I believe that opening up social institutions to forced redefinitions--as if said institutions were based on nothing more than self-satisfying, mutually agreed upon contracts--undermines their ability to support and draw the good out of those norms regarding human relationships for the benefit of society. Is that clear as mud, or what? Let me turn, as I always do when it comes to this topic, to Noah Millman, who I still believe thought it through as well as anyone ever has (scroll down a little to get to the relevant post; you should also read his original, lengthy post on the topic, here):

[Many advocates of same-sex marriage want the state to] redefine marriage to mean any exclusive partnership...between any two individuals regardless of their biological sex....That's not what marriage means, nor ever has meant, because the complementarity between men and women is at the heart of the meaning of marriage. Marriage has changed an awful lot over the centuries, and we in the West have ultimately repudiated the polygamy and consequent second-class status for women that were central to marriage for its first few thousand years as a legal institution. But the proposed redefinition would be, essentially, a linguistic falsehood. For that reason, I fear that it would have the practical consequences I identify in my original piece: because it would make the traditional language of marriage relating to complementarity of the sexes appear to be nonsensical, it would make it that much harder for men and women to learn how to relate to one another, and form stable marriages. And because it would have advanced under the banner of rights such a reform would implicitly concede that marriage is a choice rather than a norm - a choice we all have a right to make but, by the same token, the right not to make if we prefer to live otherwise.

While it's unlikely to get much of a hearing by partisans on both sides of this struggle, I would note that the above is not an argument against any kind of legally recognized same-sex marriage; it's merely an argument against our currently existing marriage regime (which is by no means the only possible set of marriage laws and understandings available either today or historically) being expanded to include same-sex couples. So what do we do for same-sex couples? We do what Noah suggested: create "a new institution...exclusively for same-sex couples, that would have many--perhaps even all--of the rights and responsibilities of marriage." Will that ever fly? Probably not; the accusations of reviving the principle of "separate but equal" would go up before the ink was even dry on any such law, assuming it ever came to pass. But if so, then perhaps that is just so much the worse for American jurisprudence. We reduce so much to either-or questions of legal rights in this country; partially by (unintentional) constitutional design, partially by inclination and habit. The sort of consensual, democratically deliberated distinctions that might emerge otherwise in the absence of such--distinctions along the lines of "distinguishing between black and white people in deciding which kind of jobs are appropriate for them is unfair and discriminatory, whereas distinguishing between gay people and straight people in determining which sort of marriage union is appropriate for them is not"--simply wouldn't survive in our legalistic environment. To quote Noah once more, "we live in an era when the hegemonic paradigm abhors difference." And, depending on the day you ask me, I might sigh and say that's the way it should be: I mean, I hardly want to throw Brown v. Board of Education out with the bathwater!

I tend to think the French were on the right track when they established PACS (pacte civil de solidarité) to serve as an alternative to marriage in order to avoid unnecessary fights with various religious communities. But they failed to articulate what they were doing as a route for gay couples in particular, and as a result the heterosexual couples looking to avoid the social implications of marriage flocked to civil unions, which warped the legislation's potential to be a model for addressing the deeper issues of "distinction" which I think are--or at least ought to--relevant here, to the extent you think any of this is worth worrying about (and, again, of all the "traditionalist" issues worth worrying about in our individualistic world, this one comes very far down the list). In any case, one last quote from Noah:

"Gay marriage" [has become] a wedge issue rather than a serious topic, and is eclipsing the serious questions about marriage. We are talking about the non-existent "threat" from gay couples instead of talking about the real damage caused by no-fault divorce. [Some] have argued, in a nutshell, that advocates for a more robust marriage culture need to focus on stopping same-sex marriage because that's (a) a popular cause, and (b) a negative trend that has to be reversed before a positive trend can be started. I can't get on that train. I can't tell a lesbian couple with children that I oppose any effort to publicly recognize their relationship because fighting them is the only way to get other straight people's attention, and that I hope, some day, to use that attention to focus on the actual problems of marriage. That's simply not just.

I agree completely...which is why, if the California proposition had moved beyond what I saw as a simply insisting upon a distinction, I wouldn't have voted for it (recognizing as I do that, especially given many of the arguments which were put into play in this election, and the expansive and diverse range of understandings at work on both sides in the huge state of California, the likelihood that anyone seeing the proposition as fundamentally an opening for democratic discussion about distinctions is pretty small).

5. And now, 3b.1--so, I would have voted against it, if it hadn't had been written in the way it was, even though my church, which I am an Sunday-attending, temple-going, life-long member of, had told me to?

Well, yes--partly because my commitment to and belief in the church doesn't ever quite override my reasoning faculties, and partly because the church leadership didn't "tell" anyone to. We are not talking about the man we hold to be a prophet (and we can leave my own personal hermeneutical consideration of what statement actually means for another time...) "commanding" anything in this case. Did our prophet, and all the rest of the church leadership (or at least, that portion of the church leadership which actually spoke out on this matter, which was actually only a tiny minority of all those who could have spoken out) want the Saints in California to vote a certain way? Absolutely, and there were statements read in California wards encouraging members of the church to organize and vote in support of the proposition, and there were references to scripture, and there were statements put out by church media, and there were directives which came down from church leaders giving advice and support to regional leaders in California who contacted members and involved them in various campaign activities, and many millions of dollars were raised along the way. But does that equal "commanded"? I don't think so. As for what happened on the local level--and rest assured, some of it was sometimes ugly--I can't comment, but the official language from Salt Lake was always one of "encouraging" the membership, not ordering them about.

Let's put it this way: Mormons in California were "expected" to vote for and help support the proposition. The question then is what kind of "expectation" we’re talking about. I am expected abstain from smoking or drinking or sleeping with anyone I'm not married to; if I do not so abstain, then by basic commitment to fundamental church doctrines and practices comes into question, and I could lose privileges as a member, or even my membership itself. Often, these kind of lay judgments (and ours is a lay church, so there are many inconsistencies along the way, I assure you) can be socially hurtful, even ostracizing, and they may involve things that have very little to do with the aforementioned fundamental church doctrines and practices. But I just can’t imagine that my bottom-line personal worthiness as a Mormon--usually measured by my receiving of a recommend allowing me to attend one of the Mormon temples--would ever be subject to sanction or judgment on such a basis. Does that mean I would have gone against the preferences of my community casually? For myself, no--I value not just my membership, but also my affectivity for, my belonging to, that community too much. But for me--and, I think, most American Mormons as well, though the majority of them (for reasons more having to do with history and demography than anything else) are already conservative enough on "culture war" issues that the church involvement in this case likely didn't make much difference in the way they were already going to vote--that belonging is just one important factor amongst many others, some equally important. Which is one more way of saying, I suppose, that I'm a liberal communitarian at heart.

Friday, November 07, 2008

Friday Morning Videos (The Kickoff): "King of Wishful Thinking"

But now, something new, something lighter, something nostalgic and fun. This Belle Waring post got me to own up to what has, over the past several months, become an enormously pleasing hobby of mine: tracking down old music videos from the 1980s or thereabouts on YouTube. They're all there, or practically all of them...it's a matter of remembering the name of that song that you woke up one morning with the tune on the cusp of your consciousness--or if not the name of the song, then the artist, or a snatch of lyrics, or something. It's all perfectly ridiculous because it's a perfect waste of time, looking for perfectly disposable bits of video art from fifteen or twenty or thirty years ago. So hell, I'm going to document it--right here, beginning today.

Why the title of this feature? Because we didn't have cable growing up, and so my original knowledge of music videos was entirely shaped by Friday Night Videos on NBC, which I would sneak into the living room and watch every week. (By my senior year, I had television of my own doubling as my computer monitor for my Commodore 64 in my room.) Friday is the end of the work week, and who so doesn't want to start their Friday with a little pop fun from a different era? I know I do.

So, for today? Well, the election was about hope, a hope that we all know will likely be dashed, perhaps numerous times, but it got us to vote anyway. And so here, in honor of hoping, is Go West's "King of Wishful Thinking." (See if you can figure out the actually rather clever sight gag at the very end.)

Thursday, November 06, 2008

Left Conservatism in a Liberal America

I agree that there are good historical reasons for seeing the election of Barack Obama as the distillation of a potentially strong and long-lasting realignment in American politics, perhaps as strong as the one which gave the Democrats dominance over the federal government for decades following FDR's election in 1932, mostly having to do the cyclical nature of such periodic alignments. But is there real data to support Judis's historical analogies? Well, there is some. Judis--along with his occasional partner, Ruy Teixeira--has been arguing for years that demographic trends in America are placing the shape and destiny of our national politics primarily into the hands of highly educated professionals (the great majority of whom work in knowledge or arts-based service industries), working and/or single women (most of whom are also college educated), and minority ethnic groups. Moreover, all of these demographic slices of the electorate are predominantly relocating to "ideopolis" urban areas--high-tech metropolitan cities surrounded by extensive exurbs, like Denver-Boulder, Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill, and so forth. And all of these trends seemed present and very much accounted for on Obama's election night. If you rank all the states on the basis of their percentage of people with advanced degrees, Obama won all of the top twenty (for 232 electoral votes alone). Nationwide, he won the votes of all women 56% to 42%, and of working women by 61% to 38% (a close to two-thirds majority). In regards to ethnic minorities, he predictably won a huge majority of the African-American vote, but he also won Hispanics and Asians by a spread of nearly or more than 30 percentage points in each case. In fact, some of the data seems to suggest that it was Obama's success with these groups alone, without any significant change in the non-Hispanic white and/or "working class" vote, that brought him the votes to win states which Kerry lost to Bush in 2004. Thus, it all seems to point in the direction of Judis-Teixeira's conclusion: the balance of electoral power is moving away from those traditional constituencies which built the primary elements of both the New Deal coalition and its predecessors, as well as the "Reagan Democrat" backlash (white, and/or European ethnic, traditional Christian, Southern and Midwestern, blue-collar and/or rural workers), and into the hands of those whose worldview, vocations, educations, and lifestyle choices are thoroughly aligned with a globalized world. In short, "the heart of the new majority is no longer blue-collar workers, but the professionals, minorities, and women who live and work within post-industrial metropolitan areas [italics added]....[Their beliefs] are socially liberal on civil rights and women's rights; committed to science and to the separation of church and state; internationalist on trade and immigration; skeptical, but not necessarily opposed to, large government spending programs, particularly on health care; and gung-ho about government regulation of business, including K Street lobbyists." This is a progressive majority that, as Ezra Klein writes, "look[s] like the America we expected to see tomorrow, not the America we remembered from yesterday."

I suppose I could be happy with this diverse and new majority; after all, it won Obama the election, and, as Matt Yglesias suggests, it may promise to win him and candidates reflective of a similar multi-racial coalition more of the same in the future. And to be sure, I'm not necessarily unhappy with all that; I particularly like--but of course, I would--Judis's acknowledgment that there is a "Naderite" streak in this new electoral grouping, in that it appears strongly committed to advocacy and participation and a distrust of those corporations and social structures which get in the way of the voices of consumers and voters being heard. But taken as a whole, I must admit I'm also a little suspicious of it, and little depressed about it. I've expressed my (perhaps desperately willed) disbelief in, and my opposition to, the Judis-Teixeira thesis several times before; I find it a condescending and misguided appreciation of what both community respect and social justice require, dealing as it does with the assumption that progressives can either count on the American working class absorbing the professional, centrist liberalism of their better-off cultural superiors, or else that they should simply plan on avoiding anything that smacks of reaching out to the (usually still church-going) working poor and lower-middle-class, both black and white (and that means unionization, anti-free trade policies, vouchers, faith-based initiatives, etc.), because doing so could turn off their new upscale electoral base.

But perhaps all this is inevitable. After years of continued globalization, years of collapse in rural populations, years of immigration, and, perhaps especially, eight years of the Bush administration--an administration that in so many ways (some intentional, some not) helped to work up the red-state/blue-state divide along class and cultural and religious lines, with the result that plenty of perfectly ordinary white middle-class exurban professionals recognized themselves in those accusatory labels: upscale, egghead, liberal elite--well, who would be surprised that the predictions of Judis and Teixeira appear to be bearing fruit, with these voters accelerating their movement towards mainstream liberal candidates? The "conservative" elements of their professional, exurban, bourgeois lives were being ignored or read out of the conservative cocoon which grew up around and through Bush's years in office. (I'm reminded of the frustrated realization felt by conservatives like John Schwenkler, Rod Dreher, or Ross Douthat when it became apparent that elements of the conservative machine had a problem with them them just for, say, assuming that everyone ought to like good healthy food, or that everyone ought to want to be exposed to different cultures, or for making the obvious point that populist politics ought to be balanced with "elite" book smarts.) Sounds like a recipe for a new majority to me, as much as I may be frustrated by parts of it. And as for the folks I tend most to trust and like, the old school, rural or ethnic populists, progressives, and New Dealers, the deep (often conflicted but always present) Laschian backbone of the 1932 (and, in an inverse way, the 1980) realignments? Well, perhaps they can be just forgotten. Why not? Doesn't this election conclusively prove that Democrats can win without the non-Hispanic white and/or working-class South, and all its white "homelander" traditionalists/populists? Perhaps it does.

But then again, maybe I shouldn't say that the liberalism of Judis and Teixeira has triumphed quite yet; maybe all that triumphed was Obama over Bush. Leaving aside the frame provided by Judis's analogies, it's clear that his victory wasn't that large of a sweep: a difference of about 7.5 million votes separated them, or about 6% of all votes cast. Besides the impressive (for Obama, anyway) developments amongst non-white voters, little fundamentally changed: the rich and the South still voted primarily for McCain, young people still didn't turn out in large numbers, and the basic red-blue geographic distribution of votes didn't change much--enough to flip a few close swing states, obviously, but not much more than that. Obama's victory did not translate into big wins in Congress. Perhaps most revealingly, on several key culture and social referendums across the country, you had a majority voters (including a fair number of white voters, of course, but in particular large majorities of religiously inclined black voters as well) supporting Barack Obama while at the same time endorsing positions that on first glance don't fit together under the umbrella of the kind of urbanized, secularized, professionalized egalitarian liberalism Judis takes his win to represent: voting against gay marriage (in California, and elsewhere) on the one hand, and for better public transportation and laws regarding the prevention of cruelty to farm animals on the other. Of course, there is one label under which I, at least, could argue that high-speed rail and traditional marriage and humane food production all fall...and that's Rod Dreher's crunchy conservatism, of which I'm a fan. But it's hardly likely that a movement as focused on things traditional and local as Rod's could really do something, ideologically or electorally speaking, with a pattern of votes like this. More likely, a different frame is going to be needed: a different way of expressing and packaging those voters which Obama picked up and which whom he shares so much ideological and demographic territory, but which also seems to reflect priorities that don't quite carry all the way through with the liberalism which Judis predicts (and has long been waiting for). It would have to draw upon the existing tendencies towards "crunchiness" out there, but which also--I hope at least--makes space for the sort of populism that Obama's liberal America, in reference to all of the above, might well touch upon, but which as yet may not be coherent enough to drawn out of him the way I'd like to think it could be.

When I first picked up the phrase "left conservatism" I was mostly just making a theoretical argument, one with only incidental relevance for actual politics; it was a frame to lump together a huge range of superficially dissimilar, but I would argue deeply connected, "socially traditionalist" and "traditionally socialist" political motivations, to use a couple of overly general labels for it. Christian social democrats, Red Tories, egalitarian populists, various "Third Way" and communitarian types--really, just about anyone who, whether they articulate it this way or not, rejects some of the more individualistic and/or secular presumptions behind many modern liberal arguments, and thus are interested community empowerment, unionization, participatory democracy, parental involvement in education, civil service, anti-consumerism, progressive taxation, media responsibility, fair trade, civic religion and respect, localized and decentralized bureaucracies, limitations on corporate power, and so forth...all could be captured by this umbrella. Obviously, it describes a very different (ideologically, at least; perhaps less so demographically) umbrella coalition of progressive voters than does Judis and Teixeira's, and--given America's political culture--a far less likely one as well. Obama, in so far as anyone can reasonably guess, wouldn't place himself under this coalition. So it's probably not going to be of any use in analyzing what happened this week and where American politics is apparently heading from this week forward; certainly it's not likely to help organize efforts to capture, respond to, or even direct the movement (however large or small) which Obama's win may (hopefully!) have begun. (Which is too bad; if that were the case, I could probably snap up a book contract real quick.)

So why bring it up? Because the crunchy cons and reactionary radicals and dissident leftists and conservative Democrats out there have a few of choices before them. They can push for legislation and initiatives and habits of behavior which may work against the demographic and socio-economic trends that Judis's analysis depends upon, so as to make that kind of liberalism less dominant in our political life and less controlling of Obama's agenda and those of his successors: stricter immigration policies, more support for rural life and blue-collar industries, a more pro-natalist tax code, etc. Let's call that Douthat's and Reihan Salam's "Reform Conservatism" option. But maybe the compromises with modernity therein are too much--and strategies involved too beholden to a party and a political language which Bush has thoroughly discredited--to really engage the scattered progressives that Judis, et al, are more than happy to lump together which what they see the new, inevitable, perhaps already-arrived America. So, instead, they can look to investing in their own local or familial retreats from the changing culture, happy to make use of the best, most progressive (in some ways) parts of it, but otherwise just hoping to tend to their own gardens. This, of course, is Dreher's "Benedict" option. It's an appealing one...but, for me at least, I think our obligation as moderns--and as Christians--to attend to and make something more justice and more beautiful and more equal out of the interconnectedness we have inherited requires more than small-scale solutions, however radical they may be and however worthy and important in their particular ways.