You can actually see me in this photo, if you look close. I'm on the left end of the second row back from the officials seated on the stage. That's where I was, at about 11am on a beautiful spring day, arranged with my fellow new PhDs on the east steps of the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, on the campus of Catholic University of America, May 12, 2001. Ten years ago today, after six years of work, I received my Doctor of Philosophy degree in Politics (none of this misleading "political science" stuff for the good folks at CUA!). At the time, I thought of it as one of the best days of my life. A decade on, I still think that way--but I have some other thoughts as well. Here are ten of them:

You can actually see me in this photo, if you look close. I'm on the left end of the second row back from the officials seated on the stage. That's where I was, at about 11am on a beautiful spring day, arranged with my fellow new PhDs on the east steps of the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, on the campus of Catholic University of America, May 12, 2001. Ten years ago today, after six years of work, I received my Doctor of Philosophy degree in Politics (none of this misleading "political science" stuff for the good folks at CUA!). At the time, I thought of it as one of the best days of my life. A decade on, I still think that way--but I have some other thoughts as well. Here are ten of them:1) It has to be said: I loved a lot about my graduate years at Catholic. No, I didn't love the financial stress, the bureaucratic hang-ups, the mounting debt, the seriously out-of-date library, the lack of student camaraderie, the retirements and relocations which made keeping in touch with my advisors a complicated affair, and more--but I loved the intellectual adventure I'd embarked upon, and all the ritual and requirements it tossed at me. I loved (most of) the faculty I worked with (and realized, unlike my undergraduate years, I could avoid the ones I didn't). I loved the cloistered feel of Catholic U., the fact that I could experience it, as a grad student, as a pleasantly run-down, idiosyncratic oasis of abstraction in the midst of a city in perpetual political motion and perpetual economic and cultural crisis. My orals, my comprehensives, my dissertation committee: I have basically positive memories of them all, despite the painful hand-cramp which my comps--two eight-hour days of nonstop writing in blue blocks--left me with. I never felt the dislike many other PhDs claim to feel for their dissertation once they finally finish with; I still take mine down from the shelf and page through it every once in a while, recognizing it as probably be the best bit of writing I've ever done or ever will do. Hell, I even enjoyed (and still remember to this day) the commencement address given on our graduation day. How much more sold on the whole experience can you get than that?

2) It also has to be said: I was really lucky, in all sorts of ways. For most others who pursue a PhD, the experience looks more like this...

...and I can't say there's anything fundamentally inaccurate with that picture either (especially sometimes inviting--but, as the years go by, more often infuriating--"just read another book!" side of the experience).

3) All of which is irrelevant to how I talk about graduate school with my students today--because I don't talk to them about it. If they bring it up, I'll happily share my feelings and experiences, and if they ask me if they should consider graduate school, I say "no." Why? For all the reasons Tim Burke thoroughly explained long ago. Tim expressed well the reality that graduate school means a complete and probably irreversible reshaping of one's intellectual expectations and cultural perspectives; his line about how graduate school is more about socialization than education--and consequently not only costs years of time, and in all likelihood many thousands of dollars (Melissa likes to refer to the student loans we've been paying off for a decade, and will keep on paying off for another 15 years or so, as "the Mercedes we'll never own"), but also almost invariably turns those who goes through it into a people that can't possibly do anything else--is so accurate, it's painful. Certainly, it was true for me (see #6, below).

4) But in case my students don't believe in something written so long ago in internet terms that it's been relocated to different servers multiple times, then I can always point them to what William Pannapacker (aka Thomas Benton) had to say about how graduate school is "structurally dependent on people who are neither privileged nor connected," which certainly describes myself at the time: a twenty-something from BYU who had dreamed for years of being some sort of professional intellectual, but had to figure out about GREs and Pell Grants and application deadlines and everything else entirely on his own, to our own disadvantage. The nature of that structural dependency is thoroughly laid out in this recent article, which everyone in academia ought to read, and ought to scare the bejeebers out of anyone thinking about trying to make a career as a professor. At best, if the student is insistent that having my kind of life--reading, writing, teaching, reviewing, blogging, advising, conference-going, committee-meeting-having--is the only one they can possibly imagine enjoying, I throw them James Mulholland's observation that going to graduate school is really kind of like "choosing to go to New York to become a painter or deciding to travel to Hollywood to become an actor," to give them a more accurate picture of what they're looking at, and then I give them my story.

5) I came out of graduate school with a vision of myself as someone who, in the years ahead, was going to further develop, and further contribute to the wider world of knowledge, my own particular specialty and expertise: the fascinating theoretical possibilities, for both politics and morality, waiting to be elaborated within the work of Johann Gottfried Herder, German philosophy, and the whole universe of romantic communitarian thought. Hence my original research agenda; hence, my original (and frankly unpronounceable) original blog title. None of that worked out.

6) My big crisis, and breakthrough, came in 2006, after five years of moving my family around to one low-paying (but, I must admit, luckily always full-time; I never had to adjunct, and perhaps that made all the difference) position after another, never making any headway, sending out hundreds of applications, struggling through dozens of phone interviews, and blessedly landing a handful of on-site visits...all of which would come to naught, and force us to find whatever was available at the last minute (no wonder the month of April always sucked). After Western Illinois said no to me, I could no longer avoid the reality: I was never going to make it as a specialist, as an expert. I wasn't lucky enough, hard-working enough, determined enough, personable enough, smart enough, insightful enough, independently-resourceful enough, racially or sexually or religiously or ideologically well-matched enough, whatever it may have been (and at one point or another along the way, it was probably all of those things), to be able to compete with all the new PhDs coming out of better schools than I went to every single year. So, it was either give up, or try again, in a different way.

7) If I have one genuine personal criticism of my graduate school experience--aside from all the systemic ones I listed above--it was this: that it didn't teach me how to be, and implicitly discouraged me from wanting to be, a generalist. I was going to be a political theorist, or so I thought; teaching comparative politics was just going to be part of the price to pay for being able to be such. While, in reality, what was necessary was someone who, somewhere in the midst of this creaky, sinking institution called "higher education" in America, was capable of providing lessons about government, economics, history, ideologies, politics, law, and foreign affairs, in the sort of contained, easily-assessable way which modern-day universities want to do, to satisfy a clientele who are looking to check off various (often state-mandated) meritocratic boxes on their way to a degree that will give them slightly more economic opportunities than they might have otherwise. I wish I'd come out of CUA knowing that; I wish I'd come out of graduate school thinking about community colleges, liberal arts institutions, anything besides universities which can afford to bless their faculty with the luxury of extensive research programs. It might have resulted in fewer wasted years, and certainly a whole lot fewer wasted dollars. But I can't blame CUA for that, really; I can blame myself, or the wholesale transformation of our education system into one which values narrowed, measurable accomplishments (all the better to outsource them, when the price is right!) over generalist and practical ones, or both--and if you want my criticisms of that, just check out here, and here, and here.

8) But in the end, I managed to make the transition, and I managed to find a niche here at Friends University five years ago, and I love it. My ideal university would be a very different sort of place, but then so would the whole education system; it would be more decentralized, less meritocratic, more permeable between the worlds of work and the academy, involve more apprenticeships and less isolation, and definitely fewer of these often mindless assessments. But Friends is a wonderful place to be, to try to figure out what it means to teach "political science" these days to a bunch of young people from Wichita, Kansas, and do it, hopefully, in my own (jumping back to CUA here!) pleasantly run-down and idiosyncratic way.

9) And here's the craziest thing: I'm still a believer in the whole enterprise, for all it cost me and for all the pain which the path that graduate school locked me onto caused my family and I over the years. I actually believe in the value and importance of someone becoming an expert on Herder (or something else), and taking up the vocation of searching for ways to translate that expertise into something that enlighten and enliven and inspire others; something that can make them better. So there's my conservatism coming out--I embrace the classic ideal of the humanities, of the arts and the sciences. I embrace, in other words, the elite ideal of being a university teacher. I embrace being able teach, first and foremost, and along the way do whatever intellectual work I can, here and there, giving up on most of the other ambitions I once held. And as for all the confusing, discouraging, class-based complications that graduate school forces you into, as part of being able to make a life doing all that? Well, I won't say it's been all worth it in some ultimate sense--maybe it hasn't. But I will say that, somehow, I've been able to survive it all so far, and I'm glad.

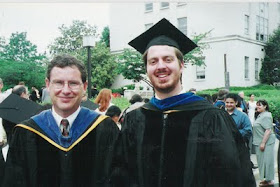

10) One final note: I didn't really earn the PhD on the wall of my office, of course. I may have done the work, but that's only because others made me into the sort of person who could. In particular, there's my graduate advisor, Steve Schneck [who happened to make it into The New York Times the day before I originally posted this; keep up the fight, Steve!]...

...my parents (who, bizarrely, always supported me in my quest to become, as my father once put it in his I'm-kidding-but-not-really way, a "parasite" upon productive society)...

...and most of all, Melissa, who for some reason thought that being the spouse of a college professor would be an attractive thing.

Man, was I blessed there. Thanks, everybody. A lot.

I still think that being the spouse of a college professor is an attractive thing. I love you!

ReplyDeleteThis is a very moving post. And wow, I'd completely forgotten about your blog's original title, despite having spent a year and a half in Heidelberg!

ReplyDeleteA quibble--you say, "but I can't blame CUA for that, really" when you talk about not being prepared to be a generalist. Really? My own department certainly didn't prepare its students to be generalists; indeed, a close friend of mine was told "never to say that out loud again, or no one will work with you" when she mentioned wanting to teach at a liberal arts school. Perhaps CUA is better about such things. But some politics departments, frankly, deserve blame.

At any rate. It's wonderful that you've ended up at Friends, and they're very lucky to have you!

Peter, I think my point wasn't to take CUA entirely off the hook, but more to assume the bulk of the blame myself. The fact is, I've known academics who came out of graduate school having properly "schooled" themselves--both in terms of personal, psychological expectations, and in terms of lesson plans ready to go--for teaching at liberal arts schools or community colleges. I wasn't one of them. Was that CUA's fault? Partly, sure, though in retrospect as see that more as a function of higher education today; I don't remember specific, directed counsel not to apply at certain schools. On the contrary, I think it was plainly, if vaguely, communicated to me that I would probably have to look everywhere for work. But I didn't prepare myself for such, and while I suppose I could fault CUA for that, I think the greater blame lies with me, for not opening my eyes to what was right before them.

ReplyDeleteAnyway, it's ten years past. Thanks for the kind words. I wish I could have spent more time in Heidelberg; we only had a summer in Frankfurt, back in 1999, and our time in Heidelberg consisted of all of one day! Not nearly enough.

In comparison to my career you have been pretty successful. I envy the fact that you have been able to find work in the US as an academic. You have also been able to keep your family physically intact. I should not complain too much because my current job at the University of Ghana is not bad. It is certainly in terms of respect, pay, and benefits much better than the one I had in Kyrgyzstan. For me getting the Ph.D. itself was well worth it. But, after returning to the US from London with a Ph.D. in 2004, my life has been far different than I imagined. I never thought I would end up in Africa.

ReplyDeleteYour post has inspired me to put up my own on the years since I got my Ph.D.

ReplyDeleteNice post, Russell. Interestingly, I came to the conclusion you eventually reached much earlier in the process--before I ever applied for a job, I figured a generalist sort of position would be my best fit. Somewhat accidently, UW prepared us for such a potentiality, given the breadth and depth of teaching experience you acquired along the way. The equivalent of your first five years were, for me, completed as an adjunct and before I got my PhD, but along the way, I developed literally dozens of classes, taught all major subfields as well as freshman writing classes, and thought I'd be reasonably well positioned for such generalist jobs as a result. I never got a second look from any of them--all the attention I ever got on the job market were from more traditional theory jobs (albeit none at a R1, research first sort of jobs). Teaching intro to Comparative regularly was part of my first (lecturer) job at Seattle U and my current job as well, but other than that I'm "the theorist" here. Still seems awfully strange to me. The whole thing underscores the folly of trying to figure out a logic or pattern to job market outcomes, I suspect.

ReplyDeleteMy expectations starting out weren't particularly high. Through most of graduate school, I never really seriously entertained the possibility that I'd actually get a tenure track job. I didn't really worry about that much, either--I was doing something interesting that I enjoyed, incurring no debt (my stipend was sufficient for my single, spartan lifestyle), and I figured I'd get the degree, try for a job, and when it didn't work out, I could adjunct for a year or two while I figured out what to do next. What I never considered was Tim Burke's very excellent point about what I was doing to myself--rendering myself unfit for most other jobs. That isn't a universal outcome for PhDs, of course, but it fits a fair number of us, including some who didn't really expect it to happen or understand or realize what was happening to them in real time. Occasionally, at moments of loneliness, I allow the thought of moving back to Seattle (to friends and family, and where I feel at home) and getting some sort of "normal job". It passes quickly, though; I love this job too much to walk away, but also "just getting a normal job" is kind of unimaginable. Not unappealing, mind you, but literally unable for me to imagine. I certainly didn't realize I was setting myself up for that when I started graduate school. I don't regret it, but I didn't quite realize the full scope of the risk I was taking, and the path I was setting myself on.

David, thanks for sharing your experiences. How interesting the fact that, in many ways, we turned out to be mirror images of each other: someone who bought entirely into the idea of becoming a specialist, who had to learn over the process of time the importance of being a generalist, versus someone who came out of graduate school with a lot of adjunct experience and fully intending on being a generalist instructor, and who yet has ended up being a specialist! Truly, your point about the "folly" of trying to make sense of it all is right on the money. And I concur entirely with your second point also; Tim Burke really did have it right when he talked about how deeply formative the graduate school experience is. Part of the reason the spring of 2006 was such a huge crisis for me was because at first I truly felt I had no decent option left except to get out of academia and do something else...and, like you, I found I could barely imagine doing anything else.

ReplyDelete