This past summer, Melissa and I, along with our two youngest girls, visited the old Fox family cabin on the Moyie river, north of Bonners Ferry, Idaho. It was the first time I or my immediate family had been to "the Moyie," as everyone in the extended family refers to it, in nearly 15 years. Unfortunately, we were only able to stay for a single night--but it was a wonderful journey out to the woods nonetheless. And it got me thinking about all the family lore which surrounds that cabin, and all the ways growing up as a Fox involved trips into the Idaho Panhandle. Of course, we're hardly alone among families in Eastern Washington making that comparatively remote corner of the Gem State our preferred playground--but nonetheless, we have enough history doing it, I think, to justify putting our stamp on it, however small it may be.

This past summer, Melissa and I, along with our two youngest girls, visited the old Fox family cabin on the Moyie river, north of Bonners Ferry, Idaho. It was the first time I or my immediate family had been to "the Moyie," as everyone in the extended family refers to it, in nearly 15 years. Unfortunately, we were only able to stay for a single night--but it was a wonderful journey out to the woods nonetheless. And it got me thinking about all the family lore which surrounds that cabin, and all the ways growing up as a Fox involved trips into the Idaho Panhandle. Of course, we're hardly alone among families in Eastern Washington making that comparatively remote corner of the Gem State our preferred playground--but nonetheless, we have enough history doing it, I think, to justify putting our stamp on it, however small it may be.

After all, growing up in Spokane--or, if you're a secessionist and must insist upon the point, the city of "Spokane Valley"--our holiday and weekend and Saturday afternoon orientation was overwhelmingly towards the east, not the west. That's not to say we never explored Washington state; we did--but not nearly as often as we would jump over the state line to enjoy the mountain wilderness which began just a couple of miles away from our home. Scout campouts at Farragut State Park, cliff jumping beneath the dam at Post Falls, fishing at Spirit Lake, skiing at Schweitzer Mountain Resort--and, in recent years, heading to Silverwood for all-day amusement; there was all of that, and more. And, of course, that's just recreation--there are family memories and histories that go beyond any of that. Here are three which come to mind.

Lake Coeur d'Alene

There are larger and deeper lakes in the Idaho Panhandle (Lake Pend Oreille), and colder and more remote ones (Priest Lake), but Lake Coeur d'Alene, whose shores we could reach from our front door--at least back in the 1980s, before the traffic around Coeur d'Alene became constantly terrible--in just 20 minutes, is the lake that we all remember best and have most often returned to, year after year after year. How many times over the decades have some combination of Fox parents, siblings, cousins, church friends, and others pile together in one car or another and make that quick drive, to swim or sail or cruise or play? Hundreds and hundreds, surely.

A lot has changed over the decades, of course. Coeur d'Alene was a sleepy town through the years I grew up. There had been a marina for fishing and sport boats there forever, obviously, but back then, before the massive resort and golf course which transformed the shoreline (which, according to Wikipedia, all happened between 1986 and 1991, which fits with my memory), you could park your cars right on the edge of the lake. The city park along its shore was rarely busy as well (the massive jungle gym/playground area there now wasn't built back then)--we'd regularly head out there with one or two families from church to grill burgers and play with Frisbees every Memorial Day, and have the place much to ourselves. And, of course, there was Wild Waters, the water-slide park right off the I-90 exit to Coeur d'Alene, where we'd spend entire summer days, sneaking our inner tubes back up the waterfall ride, and going down it again and again. It's no longer there (and honestly, good riddance; I broke a rib while speeding down one of its slides 20-odd years ago, back when I could still pretend to be a teen-ager); in its place, and all around Lake Coeur d'Alene, are restaurants and real estate offices and tourist traps galore. Yes, it's a different place.

A lot has changed over the decades, of course. Coeur d'Alene was a sleepy town through the years I grew up. There had been a marina for fishing and sport boats there forever, obviously, but back then, before the massive resort and golf course which transformed the shoreline (which, according to Wikipedia, all happened between 1986 and 1991, which fits with my memory), you could park your cars right on the edge of the lake. The city park along its shore was rarely busy as well (the massive jungle gym/playground area there now wasn't built back then)--we'd regularly head out there with one or two families from church to grill burgers and play with Frisbees every Memorial Day, and have the place much to ourselves. And, of course, there was Wild Waters, the water-slide park right off the I-90 exit to Coeur d'Alene, where we'd spend entire summer days, sneaking our inner tubes back up the waterfall ride, and going down it again and again. It's no longer there (and honestly, good riddance; I broke a rib while speeding down one of its slides 20-odd years ago, back when I could still pretend to be a teen-ager); in its place, and all around Lake Coeur d'Alene, are restaurants and real estate offices and tourist traps galore. Yes, it's a different place.

The lake, though, isn't. For all its size and all the construction that surrounds it (to say nothing of all the multi-million-dollar "vacation cabins" that adorn its distant coves and inlets, claiming bits and pieces of what once were rocks we were free to climb up and leap from), Coeur d'Alene remains a broad, beautiful, blue mountain lake, with a surprisingly fine--and only partly assisted by truck-loads of sand--beach and gorgeous cold water. It stands equal to Point Pele in Ontario and Hapuna Beach in Hawaii in my memory as one of my favorite swimming locations, and I know that's not a rare opinion among many Fox relatives. In particular, for a land-locked, Kansas-dwelling family like our own, going out on the water--whether it be for a cruise on the evening of July 4th with family, watching the fireworks shoot off from the resort, surrounded by a hundred or more other dinghies and motor-boats, with celebrating drivers and riders (and drinkers) doing the same thing, or perhaps on a rented speedboat, tearing across the lake's usually smooth surface, stopping only to dive in ourselves or to hook up an inner tube to pull at full speed behind us, then watching it skim and bounce along the water, its riders (our kids or various nieces and nephews, or maybe ourselves) laughing

The lake, though, isn't. For all its size and all the construction that surrounds it (to say nothing of all the multi-million-dollar "vacation cabins" that adorn its distant coves and inlets, claiming bits and pieces of what once were rocks we were free to climb up and leap from), Coeur d'Alene remains a broad, beautiful, blue mountain lake, with a surprisingly fine--and only partly assisted by truck-loads of sand--beach and gorgeous cold water. It stands equal to Point Pele in Ontario and Hapuna Beach in Hawaii in my memory as one of my favorite swimming locations, and I know that's not a rare opinion among many Fox relatives. In particular, for a land-locked, Kansas-dwelling family like our own, going out on the water--whether it be for a cruise on the evening of July 4th with family, watching the fireworks shoot off from the resort, surrounded by a hundred or more other dinghies and motor-boats, with celebrating drivers and riders (and drinkers) doing the same thing, or perhaps on a rented speedboat, tearing across the lake's usually smooth surface, stopping only to dive in ourselves or to hook up an inner tube to pull at full speed behind us, then watching it skim and bounce along the water, its riders (our kids or various nieces and nephews, or maybe ourselves) laughing  and holding on hysterically, trying not be thrown off--is a profound joy. Melissa in particular finds the water healing: just sitting on the beach and listening to the waves lap up and retreat, again and again, or letting her arms reach out into the spray as the boat cuts across the lake's surface, leaving its momentary wake of white churn behind it, before the lake's blue closes in on the ribbon we've cut across it once more. The is a deep beauty in finding so much of such a precious resource, all tucked away in an ancient glacier-carved valley. I couldn't have articulated that as a child, but it may partly be because Lake Coeur d'Alene has been part of my life since I was a child that I can articulate that today.

and holding on hysterically, trying not be thrown off--is a profound joy. Melissa in particular finds the water healing: just sitting on the beach and listening to the waves lap up and retreat, again and again, or letting her arms reach out into the spray as the boat cuts across the lake's surface, leaving its momentary wake of white churn behind it, before the lake's blue closes in on the ribbon we've cut across it once more. The is a deep beauty in finding so much of such a precious resource, all tucked away in an ancient glacier-carved valley. I couldn't have articulated that as a child, but it may partly be because Lake Coeur d'Alene has been part of my life since I was a child that I can articulate that today.

The Bonners Ferry Farm

The Bonners Ferry Farm

Unlike other houses and vacation spots from our family's collective memory, "the farm" never had a name that I can remember. But we all knew what it was, and where it was--tucked away in the Kootenai River valley, just north of Bonners Ferry, not far from the cabin along the Moyie--whether or not we spent much time there. Our great-grandfather, James William "Big Bill" Fox, purchased it in a land swap for some commercial property he owned in downtown Spokane in 1932, which must have been soon after the Army Corp of Engineers constructed a series of dikes to protect the bottom-land in the valley from flooding, thus enabling farming to really take off in that district. My grandfather, James Wesley "Little Bill" Fox--and thus, many years later, to me and other grandchildren, simply "Grandpa Bill" (shown standing there in the prairie grass)--worked out there as a young man, and in turn his children, including my father, did as well, helping to plow, irrigate, harvest, and--this is a favorite old story--string lines of rope across the Kootenai River so as to drag whole chicken carcasses through the water, thus helping to catch some of the huge sturgeons that swam there, long before Libby Dam was built in the early 1970s.

Who were they helping? The Amoths, a Mennonite family with whom my great-grandfather made connections long ago, and who took primary responsibility for farming the land (originally about 400 acres, but over the decades and through several acquisitions it eventually grew to nearly 1800). The Amoths weren't the first local farming family in the area, by any means; there was, in fact, an old wooden homestead cabin already standing on the property great-grandpa Bill obtained, a remnant of some even early farming settlement, no doubt dating back to when the whole valley regularly flooded. It's still there, a reminder of the history of the place, probably dating back more than century. But as for recent history, well, four generations of Amoths--first Abel, then his son Victor, then his sons Dallas and Chris, and now their children as well--have been the real story of that land. In coordination with Grandpa Bill, and then later mostly Dad, they farmed red spring wheat, winter wheat, barley, lentils, and lately alfalfa and other feed-grass for animals; for decades, the arrangement between the Amoths and our family held steady. They now do it mostly for themselves, since financial troubles forced Dad to sell off different parts of the farm in early 2010s, and Chris bought a large piece for himself. Their generations-old connection with the Fox family remains, though; Victor and Nancy were there for Dad's funeral in 2016, and when Melissa and I stopped at a grocery store in Bonners Ferry during our trip there last summer, Chris and Terry, who just happened to be there as well, saw us, invited us to visit their home and tour the farm the next day, which we did. Soon we were talking about old times, and I was able to see something which had loomed both large and distant in my memories made immediate and intimate.

Who were they helping? The Amoths, a Mennonite family with whom my great-grandfather made connections long ago, and who took primary responsibility for farming the land (originally about 400 acres, but over the decades and through several acquisitions it eventually grew to nearly 1800). The Amoths weren't the first local farming family in the area, by any means; there was, in fact, an old wooden homestead cabin already standing on the property great-grandpa Bill obtained, a remnant of some even early farming settlement, no doubt dating back to when the whole valley regularly flooded. It's still there, a reminder of the history of the place, probably dating back more than century. But as for recent history, well, four generations of Amoths--first Abel, then his son Victor, then his sons Dallas and Chris, and now their children as well--have been the real story of that land. In coordination with Grandpa Bill, and then later mostly Dad, they farmed red spring wheat, winter wheat, barley, lentils, and lately alfalfa and other feed-grass for animals; for decades, the arrangement between the Amoths and our family held steady. They now do it mostly for themselves, since financial troubles forced Dad to sell off different parts of the farm in early 2010s, and Chris bought a large piece for himself. Their generations-old connection with the Fox family remains, though; Victor and Nancy were there for Dad's funeral in 2016, and when Melissa and I stopped at a grocery store in Bonners Ferry during our trip there last summer, Chris and Terry, who just happened to be there as well, saw us, invited us to visit their home and tour the farm the next day, which we did. Soon we were talking about old times, and I was able to see something which had loomed both large and distant in my memories made immediate and intimate.

In the summer of 2004, right after the July 4th holiday, I drove to check out the farm with Dad. The wheat was tall and green, though already beginning to turn slightly yellow. Dad, as my years in Kansas have made clear to me, wasn't really a farmer; he was a businessman, an investor, a speculator, like Grandpa Bill had been--it just so happened that the arena within which they made their speculations, for many years anyway, was agricultural: grain and feed and cattle, mostly. But Dad also took seriously the tactile knowledge that makes for good speculations, and he impressed that upon me that day. Walking along a path near the Kootenai River, he pointed out the contours of the land, then dropped down on his knees, ran his hand along a stalk, took out his penknife, and separated out kernels from the head of the stalk, talking all the while about the kinds of diseases the Amoths and others have to guard against, but expressing satisfaction, nonetheless, at how full the head was.

In the summer of 2004, right after the July 4th holiday, I drove to check out the farm with Dad. The wheat was tall and green, though already beginning to turn slightly yellow. Dad, as my years in Kansas have made clear to me, wasn't really a farmer; he was a businessman, an investor, a speculator, like Grandpa Bill had been--it just so happened that the arena within which they made their speculations, for many years anyway, was agricultural: grain and feed and cattle, mostly. But Dad also took seriously the tactile knowledge that makes for good speculations, and he impressed that upon me that day. Walking along a path near the Kootenai River, he pointed out the contours of the land, then dropped down on his knees, ran his hand along a stalk, took out his penknife, and separated out kernels from the head of the stalk, talking all the while about the kinds of diseases the Amoths and others have to guard against, but expressing satisfaction, nonetheless, at how full the head was.

A little less than two years after that visit, I talked to Dad on the phone about the future of that property, and whether there could be something for me to do there with the Amoths. I thought my academic career was at an end, after having been turned down, for the second time, for a permanent job at the institution I'd been teaching at, and after five years of traveling from Virginia to Mississippi to Arkansas to Illinois, I figured it was time to fish or cut bait: to give up on my dream of being a professor--a dream that had saddled us with debt and prevented us from putting down any lasting roots--and find something else to do. I didn't really know what that "something else" might be--but even in 2006, before I became a Kansan and discovered a vocation here in a city surrounded by wheat fields and cattle lots, I suspected it might have to do with farming, with a life tied to wrestling food from the land. So I wondered about moving the family to Bonners Ferry, and becoming someone very different from whom I have--probably very much for the best--since become.

A little less than two years after that visit, I talked to Dad on the phone about the future of that property, and whether there could be something for me to do there with the Amoths. I thought my academic career was at an end, after having been turned down, for the second time, for a permanent job at the institution I'd been teaching at, and after five years of traveling from Virginia to Mississippi to Arkansas to Illinois, I figured it was time to fish or cut bait: to give up on my dream of being a professor--a dream that had saddled us with debt and prevented us from putting down any lasting roots--and find something else to do. I didn't really know what that "something else" might be--but even in 2006, before I became a Kansan and discovered a vocation here in a city surrounded by wheat fields and cattle lots, I suspected it might have to do with farming, with a life tied to wrestling food from the land. So I wondered about moving the family to Bonners Ferry, and becoming someone very different from whom I have--probably very much for the best--since become.

Like pretty much every other descendant of Bill and Edra Fox, with the legacy of the feed mill and of milking cows and raising calves and bailing hay and shucking corn and fishing trips and riding horses and so much more deep into my soul, though mostly more than three decades distant now, it's probably a little too specific to associate a passion that I realized was my own, both intellectually and practically, only in my 30s and 40s, with a farm that I've only ever visited perhaps a dozen times in my whole life. But I wonder. Agriculture isn't farmer's markets and memories of Footloose (though I learned everything I know about tractors from the latter); agriculture is the art of making productive a particular place. This place, this verdant valley north of Bonners Ferry, was a place we had--and in once having it, maybe a little bit of that productivity remains with us still, and always will.

"The Moyie"

"The Moyie"

It's a simple A-frame cabin, built by Grandpa Bill, my Dad, and my uncle Bob Church (who married Dad's older sister Marilyn), in a lot which Grandpa had purchased along the Moyie River (the land surrounding it is partly national forest, and partly owned by the Burlington Northern railroad; I've no idea when or how those particular lots along the river became available). Now that everyone who was involved in the building of the cabin has passed away, nailing down specific historical details is difficult. Very likely the cabin was built entirely in the summer of 1971. Originally it had a plain, open bottom floor, divided between three rooms--a bedroom, a kitchen, and a living room with a round, indoor fireplace whose chimney extended through the roof--and a half second-floor that was entirely open, and accessible only by a wooden staircase that could be raised or lowered by ropes. Within a year, improvements began: an attached bathroom (so no more need to use "Big John," the outhouse out back, which became a source of jokes and vague nighttime terrors for us grandkids for decades to come), and a circular metal staircase to replace the long wooden one. (This is actually a real surprise to me, as I'm certain I can remember the wooden staircase, which means I have memory from when I was less than three years old.) In the years to come, the upstairs was enclosed and divided into two different bedrooms, and the central wood stove eventually fell out of use and was locked. But those alterations didn't change the basics. This glorious little A-frame cabin, with its combination of hominess (Grandma's years of copies of Reader's Digest magazines! Decades of accumulated fishing gear!) and isolation (not so much now, with so many other cabins along the Moyie having been decked out with satellite dishes and permanent mailboxes, but for a long time, between the turn-off at the Good Grief, Idaho, tavern and the cabin, there was pretty much nothing but an old railroad junction, a bridge with warning signs about truck weight, and a lot of spooky woods) became a weekend and summer vacation home for the whole extended clan, giving rise of thousands of memories.

Most involve the river--which seemed a lot more impressive when I was little, but even as recently as this summer, could be the stuff of wonderful and (often hilarious) wilderness fantasies. The part directly in front of the cabin is pretty slow moving, but that hasn't stopped it from, when the winter run-off is good, being deep enough to wade, wash, and occasionally catch catfish with your bare hands in. It's a cold mountain river, and thus has, for many years, served as a first rate spot for storing soda or watermelons to be eaten later in the day. On the other side of the river runs the railroad, and generations for Fox kids have rushed down to the river's edge in the morning as the train comes by, miming for the driver to pull the train's horn (they usually succeed).

Most involve the river--which seemed a lot more impressive when I was little, but even as recently as this summer, could be the stuff of wonderful and (often hilarious) wilderness fantasies. The part directly in front of the cabin is pretty slow moving, but that hasn't stopped it from, when the winter run-off is good, being deep enough to wade, wash, and occasionally catch catfish with your bare hands in. It's a cold mountain river, and thus has, for many years, served as a first rate spot for storing soda or watermelons to be eaten later in the day. On the other side of the river runs the railroad, and generations for Fox kids have rushed down to the river's edge in the morning as the train comes by, miming for the driver to pull the train's horn (they usually succeed).

But the real river memories, I think, all involving rafting down the river--and while the low and placid character of long stretches of the Moyie--with it sometimes shallow enough you need to get out and pull your raft, canoe, or rowboat off of sandbars--might make you think it's an easy trip, there are enough small rapids along the way to give 6, or 9, or even 14-year-olds some real moments of panic. Especially on the longer journeys--I can remember once traveling down the river in a rubber raft all the way from the Canadian border about 7 miles north of the cabin; it was a grey and cloudy day, and at one point a cold rain fell, and the trip took hours of negotiating deadfalls, hidden rocks, and rapids that left us all soaked. I'm positive I was crying by the end--I suspect I was around 10-years-old at the time, at most--but now, decades later, I consider it a mighty adventure.

But the real river memories, I think, all involving rafting down the river--and while the low and placid character of long stretches of the Moyie--with it sometimes shallow enough you need to get out and pull your raft, canoe, or rowboat off of sandbars--might make you think it's an easy trip, there are enough small rapids along the way to give 6, or 9, or even 14-year-olds some real moments of panic. Especially on the longer journeys--I can remember once traveling down the river in a rubber raft all the way from the Canadian border about 7 miles north of the cabin; it was a grey and cloudy day, and at one point a cold rain fell, and the trip took hours of negotiating deadfalls, hidden rocks, and rapids that left us all soaked. I'm positive I was crying by the end--I suspect I was around 10-years-old at the time, at most--but now, decades later, I consider it a mighty adventure.

It occurs to me now that the decades-old Fox family tradition of putting relatively young people out on the water (often without life jackets) almost certainly runs afoul of any number of Idaho state rules about river use--but then, I can't recall anyone ever running into any kind of state official anywhere on the Moyie, so if those rules actually exist, they're obviously not enforced. And would we have acknowledged them the moment any such hypothetical officer turned aside, after handing out a warning? Given our love of water fights on the river, and challenging each other to ridiculous stunts while out on the boats, I'd say probably not. This was our retreat, our isolated compound, our natural playground: if we wanted to toss fireworks into the river when we made the woods around the cabin echo with explosions on July 4th, or shoot them off the edge of the aforementioned bridge, who was to say no?

The same goes for the woods all around us. There were, of course, plenty of well-marked trails to follow throughout the Kootenai National Forest--but were those the ones we used? In my memory, mostly no--instead we took off up into the mountains, looking for the legendary miner's cabin (which, I have since learned from some of my cousins, you can apparently just drive to, if you know the right turn-offs), or the borderline racistly mis-named Chinese Dam (actually Eileen Dam, which has been a ruin--as well as a nigh-inaccessible and consequently much prized mountain swimming retreat--for nearly a century; the name the Fox kids and grandkids passed down among themselves for the dam probably started with Grandpa Bill, who must have somehow connected the story of dam's construction in the 1920s with the impoverished Chinese laborers the railroad companies used back then). My own record on these adventures in the woods is mixed. I never have managed to find the miner's cabin, despite hiking through the Idaho backwood's on one occasion decades ago for an entire day, only discovering too late that we'd actually been going up the wrong mountain entirely. As for Eileen Dam, though, I remembered our visit to that glorious, remote, wonderfully cold and deep swimming spot well, and was able to take my family to it this past summer--it hadn't changed much in the 30 years or so since I'd swum there last. No doubt the track record of many other members of the extended Fox clan is much better.

The same goes for the woods all around us. There were, of course, plenty of well-marked trails to follow throughout the Kootenai National Forest--but were those the ones we used? In my memory, mostly no--instead we took off up into the mountains, looking for the legendary miner's cabin (which, I have since learned from some of my cousins, you can apparently just drive to, if you know the right turn-offs), or the borderline racistly mis-named Chinese Dam (actually Eileen Dam, which has been a ruin--as well as a nigh-inaccessible and consequently much prized mountain swimming retreat--for nearly a century; the name the Fox kids and grandkids passed down among themselves for the dam probably started with Grandpa Bill, who must have somehow connected the story of dam's construction in the 1920s with the impoverished Chinese laborers the railroad companies used back then). My own record on these adventures in the woods is mixed. I never have managed to find the miner's cabin, despite hiking through the Idaho backwood's on one occasion decades ago for an entire day, only discovering too late that we'd actually been going up the wrong mountain entirely. As for Eileen Dam, though, I remembered our visit to that glorious, remote, wonderfully cold and deep swimming spot well, and was able to take my family to it this past summer--it hadn't changed much in the 30 years or so since I'd swum there last. No doubt the track record of many other members of the extended Fox clan is much better.

Of course, this is all outside-the-cabin stuff; it is ignoring the ghost stories around the campfire, the Risk games around the kitchen table going for all hours (one day at the Moyie long ago being the only time in my whole life that I managed to beat all my brothers at Risk, and with the out-of-Australia strategy too, if you can believe that), the midnight walks with other family members trying to scare you along the way, the craft projects for the little kids, the tinfoil dinners cooked in the fire pit, the weekend trips dedicated to nothing but Dungeons & Dragons, the fights with flaming sticks while cooking shish-kebabs on the fire, the constant need for ad-hoc medical assistance as we (and later our children) all encountered poison ivy, hornets, and other assorted creatures (to say nothing of the aforementioned flaming sticks), the hours of quiet reading time (at the Moyie, at least, there is no landline, no internet, and no data), the sunrises slowly lighting the wooded glade around the cabin, and the family gatherings as the years and decades have gone by. There are great and important memories associated with that cabin, tucked away in mountains of northern Idaho, some playful, some spiritual, some personal, some a little bit of both. Missions, marriages, and more have been shaped by the time the Foxes have spent in that little A-frame, usually for better, or so I hope. It's been part of our private Idaho history for nearly a half-century, and I hope it will be able to remain part of our stories for many years to come.

Of course, this is all outside-the-cabin stuff; it is ignoring the ghost stories around the campfire, the Risk games around the kitchen table going for all hours (one day at the Moyie long ago being the only time in my whole life that I managed to beat all my brothers at Risk, and with the out-of-Australia strategy too, if you can believe that), the midnight walks with other family members trying to scare you along the way, the craft projects for the little kids, the tinfoil dinners cooked in the fire pit, the weekend trips dedicated to nothing but Dungeons & Dragons, the fights with flaming sticks while cooking shish-kebabs on the fire, the constant need for ad-hoc medical assistance as we (and later our children) all encountered poison ivy, hornets, and other assorted creatures (to say nothing of the aforementioned flaming sticks), the hours of quiet reading time (at the Moyie, at least, there is no landline, no internet, and no data), the sunrises slowly lighting the wooded glade around the cabin, and the family gatherings as the years and decades have gone by. There are great and important memories associated with that cabin, tucked away in mountains of northern Idaho, some playful, some spiritual, some personal, some a little bit of both. Missions, marriages, and more have been shaped by the time the Foxes have spent in that little A-frame, usually for better, or so I hope. It's been part of our private Idaho history for nearly a half-century, and I hope it will be able to remain part of our stories for many years to come.

Of course a cabin is just a building, a place where people gather, so at least in theory we could share any number of those exact same memories with any place where the Foxes have spent time over the years. Similarly, a lake is just a hole with water in it, and a farm is just soil that has plants growing on it. But that theory, as we all well know, doesn't quite match reality. The reality is that there really are places where the piling up of history and associations is so great that the places themselves start to do some of your own remembering for you, making what happens there meaningful almost without your realizing it. How very blessed our family is have these little slices of shared experiences, these little bits of the Gem State, as part of our lives. They all, of course, have their own complex existence--ecological, economic, and otherwise--entirely apart from the extended Fox clan's uses of them as well. Still, with them and around them, we can make plans, make references, make our trips from our eastern Washington home bases, and find them waiting for us, rewarding us with things--fun, adventure, exploration, relaxation, information, reminders of days gone by--that, in a small but important way, is actually, already our own. As Goethe had Faust say: "Was du ererbt von deinen Vätern hast / Erwirb es, um es zu besitzen"--"What from your fathers you received as heir / Acquire anew if you would possess it." Hopefully the Foxes will keep re-acquiring, and keep re-remembering, our own private Idaho for a long time to come.

Of course a cabin is just a building, a place where people gather, so at least in theory we could share any number of those exact same memories with any place where the Foxes have spent time over the years. Similarly, a lake is just a hole with water in it, and a farm is just soil that has plants growing on it. But that theory, as we all well know, doesn't quite match reality. The reality is that there really are places where the piling up of history and associations is so great that the places themselves start to do some of your own remembering for you, making what happens there meaningful almost without your realizing it. How very blessed our family is have these little slices of shared experiences, these little bits of the Gem State, as part of our lives. They all, of course, have their own complex existence--ecological, economic, and otherwise--entirely apart from the extended Fox clan's uses of them as well. Still, with them and around them, we can make plans, make references, make our trips from our eastern Washington home bases, and find them waiting for us, rewarding us with things--fun, adventure, exploration, relaxation, information, reminders of days gone by--that, in a small but important way, is actually, already our own. As Goethe had Faust say: "Was du ererbt von deinen Vätern hast / Erwirb es, um es zu besitzen"--"What from your fathers you received as heir / Acquire anew if you would possess it." Hopefully the Foxes will keep re-acquiring, and keep re-remembering, our own private Idaho for a long time to come.

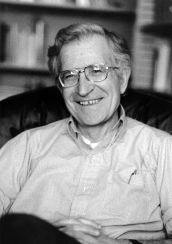

The above characters, in spoken Chinese, are "Wǔshí ér zhī tiānmìng"--but I can't speak Chinese, so that is irrelevant. What is relevant is the phrase's meaning: "At 50 I knew the mandate of heaven." It is the fifth clause in perhaps the most famous passage from Confucius's Analects, found in Book 2, Line 4: "The Master said: 'At fifteen my heart was set on learning; at thirty I

stood firm; at forty I was unperturbed; at fifty I knew the mandate of

heaven; at sixty my ear was obedient; at seventy I could follow my

heart's desire without transgressing the norm.'" The master is Confucius, of course (the photo above is of a statue of him in Nanjing, China, which I took in 2014). Did he actually express this personal biography. Doubtful, but it's really impossible to say.

The above characters, in spoken Chinese, are "Wǔshí ér zhī tiānmìng"--but I can't speak Chinese, so that is irrelevant. What is relevant is the phrase's meaning: "At 50 I knew the mandate of heaven." It is the fifth clause in perhaps the most famous passage from Confucius's Analects, found in Book 2, Line 4: "The Master said: 'At fifteen my heart was set on learning; at thirty I

stood firm; at forty I was unperturbed; at fifty I knew the mandate of

heaven; at sixty my ear was obedient; at seventy I could follow my

heart's desire without transgressing the norm.'" The master is Confucius, of course (the photo above is of a statue of him in Nanjing, China, which I took in 2014). Did he actually express this personal biography. Doubtful, but it's really impossible to say.

Alexander

Alexander  Listeners of radio’s Columbia Broadcasting System who tuned in to hear a Christmas Eve rendition of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol were shocked when they heard what appeared to be a newscast from the north pole, reporting that Santa’s Workshop had been overrun in a blitzkrieg by Finnish proxies of the Nazi German government. The newscast, a hoax created by 20-something wunderkind Orson Wells as a seasonal allegory about the spread of Fascism in Europe, was so successful that few listeners stayed to listen until the end, when St. Nick emerged from the smoking ruins of his workshop to deliver a rousing call to action against the authoritarian tide and to urge peace on Earth, good will toward men and expound on the joys of a hot cup of Mercury Theater of Air’s sponsor Campbell’s soup. Instead, tens of thousands of New York City children mobbed the Macy’s Department Store on 34

Listeners of radio’s Columbia Broadcasting System who tuned in to hear a Christmas Eve rendition of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol were shocked when they heard what appeared to be a newscast from the north pole, reporting that Santa’s Workshop had been overrun in a blitzkrieg by Finnish proxies of the Nazi German government. The newscast, a hoax created by 20-something wunderkind Orson Wells as a seasonal allegory about the spread of Fascism in Europe, was so successful that few listeners stayed to listen until the end, when St. Nick emerged from the smoking ruins of his workshop to deliver a rousing call to action against the authoritarian tide and to urge peace on Earth, good will toward men and expound on the joys of a hot cup of Mercury Theater of Air’s sponsor Campbell’s soup. Instead, tens of thousands of New York City children mobbed the Macy’s Department Store on 34 In this hour-long radio drama, Santa struggles with the increasing demands of providing gifts for millions of spoiled, ungrateful brats across the world, until a single elf, in the engineering department of his workshop, convinces Santa to go on strike. The special ends with the entropic collapse of the civilization of takers and the spectacle of children trudging across the bitterly cold, dark tundra to offer Santa cash for his services, acknowledging at last that his genius makes the gifts — and therefore Christmas — possible. Prior to broadcast, Mutual Broadcast System executives raised objections to the radio play, noting that 56 minutes of the hour-long broadcast went to a philosophical manifesto by the elf and of the four remaining minutes, three went to a love scene between Santa and the cold, practical Mrs. Claus that was rendered into radio through the use of grunts and the shattering of several dozen whiskey tumblers. In later letters, Rand sneeringly described these executives as “anti-life.”

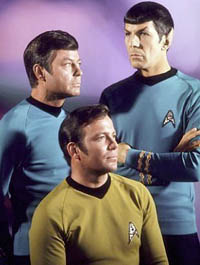

In this hour-long radio drama, Santa struggles with the increasing demands of providing gifts for millions of spoiled, ungrateful brats across the world, until a single elf, in the engineering department of his workshop, convinces Santa to go on strike. The special ends with the entropic collapse of the civilization of takers and the spectacle of children trudging across the bitterly cold, dark tundra to offer Santa cash for his services, acknowledging at last that his genius makes the gifts — and therefore Christmas — possible. Prior to broadcast, Mutual Broadcast System executives raised objections to the radio play, noting that 56 minutes of the hour-long broadcast went to a philosophical manifesto by the elf and of the four remaining minutes, three went to a love scene between Santa and the cold, practical Mrs. Claus that was rendered into radio through the use of grunts and the shattering of several dozen whiskey tumblers. In later letters, Rand sneeringly described these executives as “anti-life.” Mr. Spock, with his pointy ears, is hailed as a messiah on a wintry world where elves toil for a mysterious master, revealed to be Santa just prior to the first commercial break. Santa, enraged, kills Ensign Jones and attacks the Enterprise in his sleigh. As

Mr. Spock, with his pointy ears, is hailed as a messiah on a wintry world where elves toil for a mysterious master, revealed to be Santa just prior to the first commercial break. Santa, enraged, kills Ensign Jones and attacks the Enterprise in his sleigh. As  This ABC Christmas special featured Santa as a happy-go-lucky swinger who comically wades into the marital bed of two neurotic 70s couples, and also the music of the Carpenters. It was screened for television critics but shelved by the network when the critics, assembled at ABC’s New York offices, rose as one to strangle the producers at the post-viewing interview. Joel

This ABC Christmas special featured Santa as a happy-go-lucky swinger who comically wades into the marital bed of two neurotic 70s couples, and also the music of the Carpenters. It was screened for television critics but shelved by the network when the critics, assembled at ABC’s New York offices, rose as one to strangle the producers at the post-viewing interview. Joel  A year before their rather more successful Christmas pairing with John Denver, the

A year before their rather more successful Christmas pairing with John Denver, the  Undeterred by the miserable flop of the movie Can’t Stop the Music!, last place television network NBC aired this special, in which music group the Village People mobilize to save Christmas after Santa Claus (Paul Lynde) experiences a hernia. Thus follows several musical sequences — on ice! — where the Village People move Santa’s Workshop to Christopher Street, enlist their friends to become elves with an adapted version of their hit “In The Navy,” and draft film co-star Bruce Jenner to become the new Santa in a sequence which involves stripping the 1976 gold medal decathlon winner to his shorts, shaving and oiling his chest, and outfitting him in fur-trimmed red briefs and crimson leathers to a disco version of “Come O Ye Faithful.” Peggy Fleming, Shields and

Undeterred by the miserable flop of the movie Can’t Stop the Music!, last place television network NBC aired this special, in which music group the Village People mobilize to save Christmas after Santa Claus (Paul Lynde) experiences a hernia. Thus follows several musical sequences — on ice! — where the Village People move Santa’s Workshop to Christopher Street, enlist their friends to become elves with an adapted version of their hit “In The Navy,” and draft film co-star Bruce Jenner to become the new Santa in a sequence which involves stripping the 1976 gold medal decathlon winner to his shorts, shaving and oiling his chest, and outfitting him in fur-trimmed red briefs and crimson leathers to a disco version of “Come O Ye Faithful.” Peggy Fleming, Shields and  Faced with Canadian content requirements but no new programming, the Canadian Broadcasting Company turned to Canadian director David

Faced with Canadian content requirements but no new programming, the Canadian Broadcasting Company turned to Canadian director David  This PBS/

This PBS/